By Rod Nordland

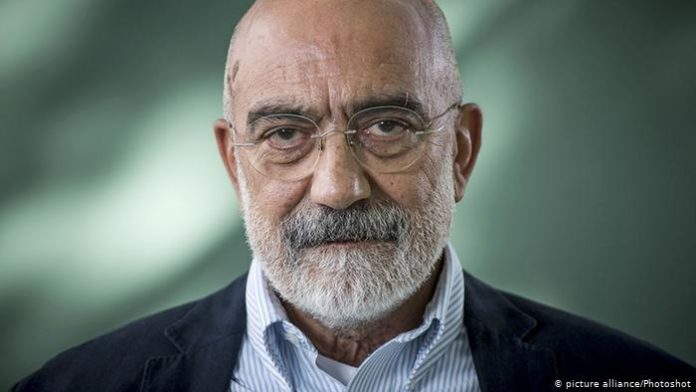

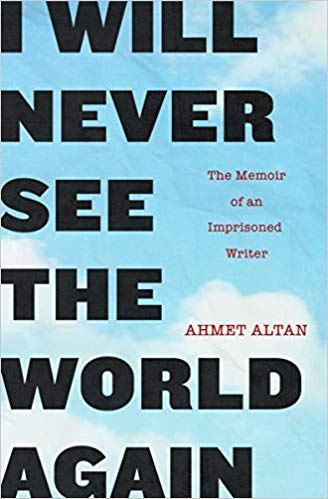

The Turkish novelist and journalist Ahmet Altan is serving a life sentence in prison in his home country, allowed to see his children only occasionally and his writing, in theory, limited to short notes to his family and lawyers. Earlier this month, however, Other Press published the English translation of his memoir, “I Will Never See the World Again,” which was written behind bars, defiantly, and smuggled out to that world he will never see.

I feel a special sort of empathy with Mr. Altan because I too am facing a life sentence — a terminal disease in the form of an often fatal form of brain tumor — but in my case at least I can blame health, God or bad fortune rather than my own vindictive countrymen.

Here it must be said that the title of Mr. Altan’s book is the statement of a brutal fact, rather than a cry of despair. There is not a smidgen of self-pity in the memoir’s 212 pages. What emerges is this: You cannot jail my mind, and you cannot shut me up. “I have never woken up in prison, not once,” he writes. “I am writing this in a prison cell and I am not in prison. I am a writer.”

If Mr. Altan, who at 69 is in his third year in prison, defies the degradations of prison life, he also doesn’t minimize them. He writes about “the fires of terror,” as he calls them; the pernicious process of dis-individuation; the substitution of his normally unused birth certificate name for the one he is usually known by; and the replacement of his clothing for a uniform. He cannot dress or undress, eat, bathe or exercise when he pleases. But one of the harshest privations is a surprising one: There are no mirrors or even reflective surfaces anywhere in his prison campus, which houses an astonishing 11,000 prisoners, most of them there for political reasons.

He had not previously realized how often one contemplates one’s own reflection, or how important it is. “Making eye contact with yourself is a small miracle,” he writes. “I looked around, searching for myself, and I wasn’t there.”