By Robert Fisk

I rarely have reason to thank Turkish ambassadors. They tend to hold a different view of the 1915 Armenian holocaust, in which a million and a half Armenian Christians were deliberately murdered in a planned genocide by the Ottoman Turkish regime. “Hardship and suffering”, they agree, was the Armenians’ lot. But genocide? Never.

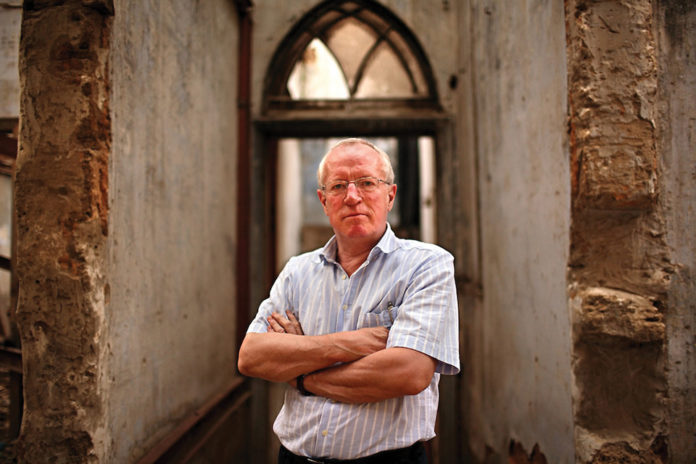

Well, that’s not the view of genocide scholars — including Israeli historians — nor of that bravest of Turkish academics, Taner Akçam, who has prowled thorough the Ottoman archives to find the proof. The Armenians did suffer, alas, a genocide.

Certainly my gratitude to His Excellency Umit Yalcin, Turkish ambassador to the Court of St James, is not for his letter to me, in which he describes the Armenian genocide as a “one-sided narrative”. But he did enclose a small book, published five years ago by Edward Erickson, whose contents obfuscate the details of the mass slaughter of the Armenians, even daring to suggest that the Ottoman “strategy of population relocation” should be seen in the contemporary setting of Britain’s policy of “relocating” civilians in the Boer War (in “concentration camps”) in South Africa, and by the Americans in the Philippines.

Interesting. But we didn’t mass rape the Boer women, burn their children and drown Boer men in rivers.

Erickson was an American army colonel and is now professor of military history at the Marine Corps University in Virginia. He insists that there was a widespread Armenian insurgency at the time of the killings. A fine Kurdish scholar has described his book Ottomans and Armenians: A Study in Counterinsurgency as “rich” in sources, but insists that these sources are distorted. Akçam himself says that even if Erickson’s contention that there was a real Armenian insurgency in Turkey (which Akçam disputes) was true, this would only explain why the genocide happened — not why it never occurred!