By Oliver Bullough

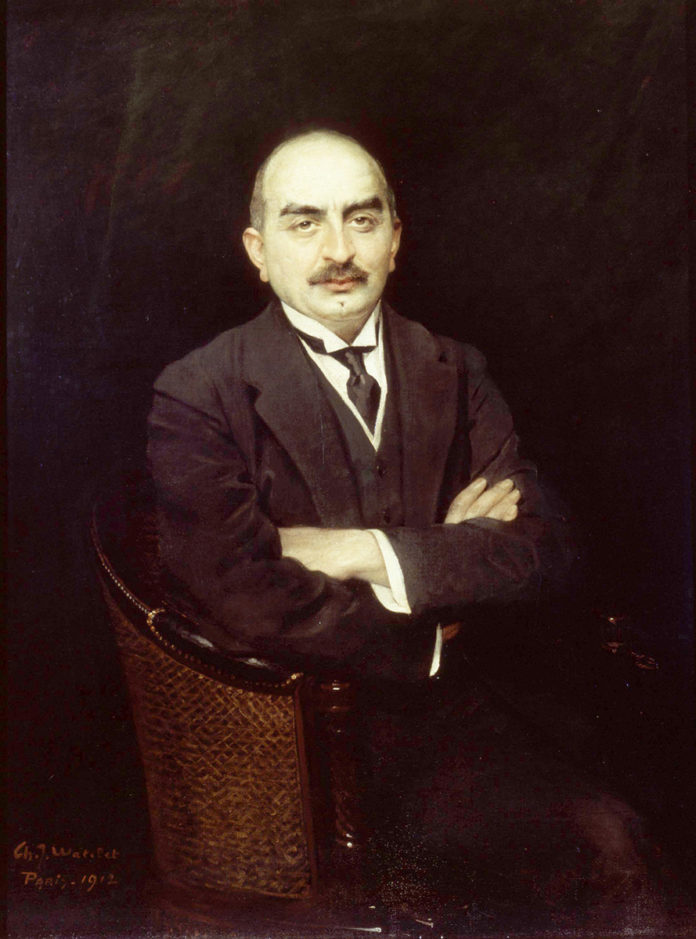

What does the life of an Ottoman-born ethnic Armenian oil tycoon have to teach us about the modern world? Quite a lot, it turns out, judging by this fascinating biography of Calouste Gulbenkian, a dealmaker for the ages and, at his death in 1955, the world’s richest man.

Gulbenkian saw an oilfield only once, on a visit to Baku (then an oil-fueled boomtown in the Russian empire, now the capital of Azerbaijan) as a 19-year-old graduate from King’s College London, but he was very quick to appreciate the importance of oil as a commodity, and the opportunity inherent in international competition for it. He combined excellent contacts in the Middle East with skills he learned as an entrepreneur in the City of London, and secured a 5% stake in all oil found beneath the Asian territories of the Ottoman empire.

When the deal was signed, on the eve of the first world war, his stake didn’t sound like much, but he fought for decades to hang on to it and, by the 1950s, he had a shilling for every pound earned from some of the world’s richest oilfields. And that really added up. In modern terms, he died with a fortune of almost £5bn.

He was clearly not an easy person to like, and fell out with almost everyone he came across, but his buccaneering qualities make him an extremely interesting person to read about. At one point, he exploited the young Soviet Union’s shortage of capital to build the nucleus of a world-class art collection. There are several Rembrandts missing from the Hermitage, thanks to his negotiating skills.

When Gulbenkian was born in 1869, Armenians were a significant minority in Istanbul, and dominated the city’s commercial sector, having taken advantage of a series of reforms passed by an Ottoman government keen to expand its decrepit economy. By the 1880s, however, the city was becoming uncomfortable for them, with the start of a wave of pogroms that peaked in the infamous Armenian genocide of 1915-17.