WATERTOWN — The long shadow the Armenian Genocide has cast on the lives of those in the Armenian Diaspora is brought to light in the exhibition “Reimagining a Lost Homeland: Ottoman Era Photographs from the Dildilian Studio.”

The exhibit, put together from the personal collection of Prof. Armen T. Marsoobian, opened at the Armenian Museum of America on January 8 and will go on through April 2. It is co-sponsored by Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archives.

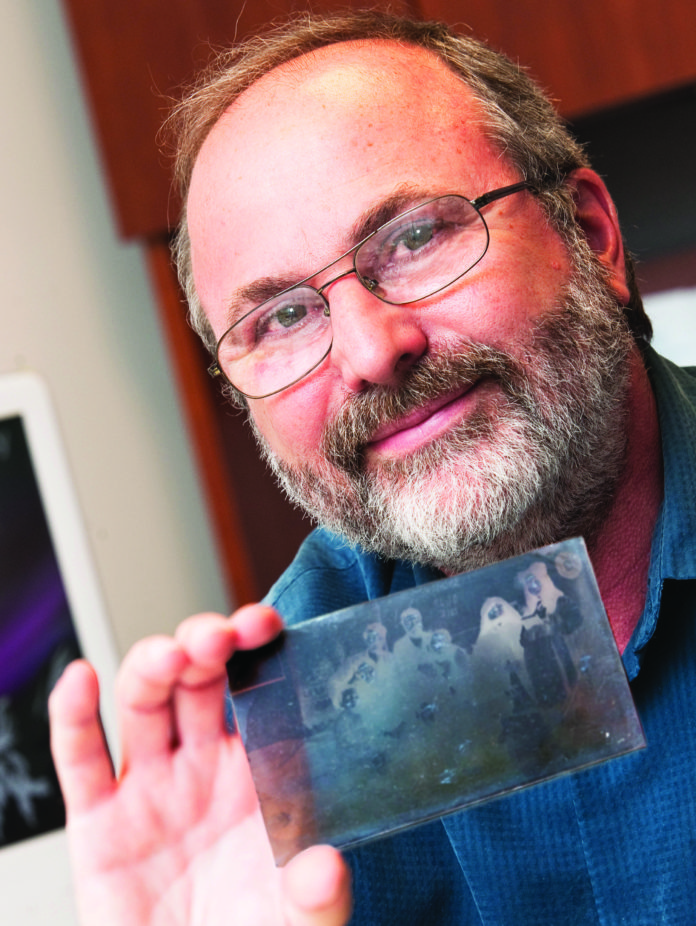

Marsoobian, a professor of philosophy as well as the Philosophy Department Chair at Southern Connecticut State University, is a grandchild of Tsolag Dildilian, who along with his brother, Aram, owned and operated the Dildilian Brothers Studio in Anatolia. He has been the de facto keeper of family photographic archives.

The exhibit is an offshoot of the book Marsoobian wrote about his maternal ancestors, titled Reimagining a Lost Homeland: The Dildilian Brothers Photography Collection.

In essence, Marsoobian said, the family has taken photos for 100 years, capturing much of Armenian life in the Ottoman Empire.

Unlike many families where the stories of the Armenian Genocide and survival were repressed, in his family, “the stories were told again and again. My parents told us about what happened and I started to see many of the photos during family reunions. Most of it was with my uncle in Hartford. As he declined in health, he started to give me the material and hoped I would preserve it and do something with it.”