By Daphne Abeel

Special to Mirror-Spectator

Last year, photographer Yousuf Karsh’s repu- tation in the Boston area received a special boost when his widow, Estrelita, made a gift of 27 of his best-known images to the Armenian Library and Museum of America (ALMA) in Watertown. The images, which are now part of ALMA’s permanent collection, ensure that Karsh will have a lasting presence in one of the Armenian community’s more important institu- tions.

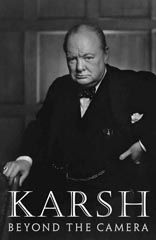

Now, David R. Godine Publishers, known for its high production values, has, again with the support and encouragement of Estrelita Karsh, assembled a collection of nearly 70 images, accompanied with a dual text: commentary by Karsh himself on his subjects, and additional interpretation and commentary by David Travis, the founder of the Department of Photography at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The comments by Karsh have been extracted from a series of interviews, which were conducted in 1988 by Jerry Fiedler, Karsh’s long time studio assistant, who sat down with the master and taped many hours of reminiscences and recollections regarding his subjects and the conditions in which he made his pictures.