By Aram Arkun

Mirror-Spectator Staff

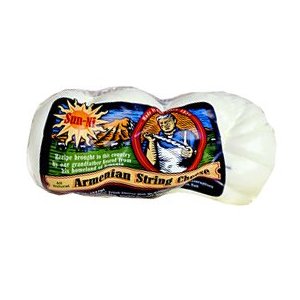

PHILADELPHIA — For many Armenians, food is one of the most fundamental elements of their identity. Thus, making Armenian food accessible and known in the United States contributes in a modest way toward preserving an aspect of Armenian culture, and Monica Whitcomb and the Sun-Ni Cheese Company play a role in that process. The Sun-Ni Cheese Company, located in Wayne, a suburb of Philadelphia, is one of the leading makers of Armenian string cheese in the United States.

The company was founded through the efforts of Kosrof Der Ohanessian, an Armenian native of Arapgir or Arapkir in the Ottoman Empire. As a young boy who lost most of his family in the Armenian Genocide, he came to the US in 1925 via Cuba and Canada. He had some distant relatives in Philadelphia, which at the time was a big center for Arapkir Armenians. He worked at a variety of jobs for several decades

until he was able to open a delicatessen with a friend in the 1960s. Even before this, he and a friend would make string cheese in his kitchen for fellow Armenians. However, according to his granddaughter, Monica Whitcomb, he began to experiment and tried to Americanize its taste. It was too salty and