By Guillermo Carvajal

YEREVAN (LBV Magazine) — A team of Armenian and European researchers has carried out the first comprehensive statistical analysis of the vishaps, enigmatic prehistoric stelae known as “dragon stones” that rise in the highlands of Armenia. The results, published in the journal Npj Heritage Science, reveal that their construction was an intentional and colossal effort, and that they were deeply linked to an ancient water cult.

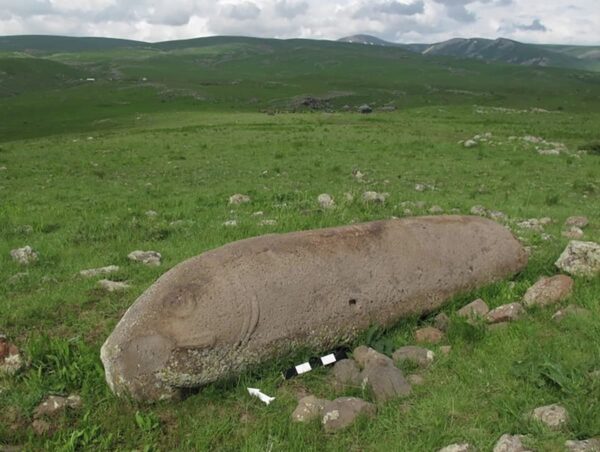

The vishaps (Armenian term for “dragon”) are prehistoric stone monuments carved with images of animals. They are found in the high mountain pastures of present-day Armenia and adjacent regions, at altitudes ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 meters above sea level. Carved from local stone, mainly andesite and basalt, these stelae are classified into three main types: Piscis: Fish-shaped, Vellus: Shaped like a stretched or hanging bovine hide and Hybrid: A combination of the iconographies of the two previous types.

With heights ranging from 1.1 to 5.5 meters, most lie today toppled or placed horizontally, but the fact that all of them are carved and polished on all sides except for the “tail” strongly indicates that they were originally erected vertically.

A Century-old Archaeological Puzzle

Scientific interest in the vishaps arose in the early 20th century. The scholar Ash-Kharbek Kalantar pioneered their study in an archaeological context and linked them with other megalithic phenomena. He was the one who launched a crucial hypothesis: that the vishaps marked critical points in prehistoric irrigation systems.