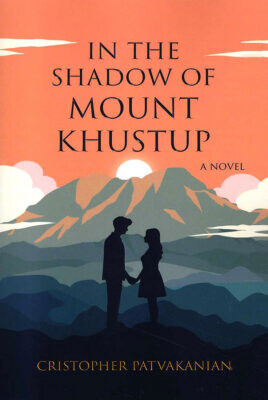

Christopher Patvakanian’s debut novel In The Shadow of Mount Khustup (2025) delights the reader with the flawless beauty of the red poppies and the bright greens of the beloved Zangezur mountains in Syunik, the southernmost province of the Republic of Armenia. We rejoice in the spring sunshine and the snow on the slopes of Mount Khustup, the focal point of the skyline of the city of Kapan where Khatchik Lazaryan, the 26-year-old engineer from Yerevan, moves to work as a safety engineer at the KapanQar Mining Company so that he can help pay for his father’s hospitalization, who had been injured fighting in the 2020 44-day Artsakh War. Khatchik returns to the smell of burning wood and “the aroma of something delicious cooking somewhere“ of his native village Jrashenik. He comes back to the khash breakfasts, the barbecues and the endless drinking and toasting with the qashats aragh, their homemade vodka. “There was no night like a village night,” writes Patvakanian.

Although not dealt with directly, the trauma of the war is ever present. Kapan is close to the tense Armenia-Azerbaijan border. Those fallen in combat in the Artsakh War and the ordeal of an entire population being forced out of its ancestral lands loom large in the background. The celebratory drinking and the toasts inevitably recall the “lots of faces missing.” Khatchik will forever miss his brother Gabriel, who was killed fighting in the war. He will miss his father lying in a coma in a hospital bed in Yerevan, battling to survive.

“Paradise” has been lost, yet Khatchik knows that “the healing power of his clan” could make Jrashenik “home” for anyone. Haso horqur greets him with “yekal es ton,” “Another dear soul returns home.” All love and support their zarmik. “As much as home could be a place, a physical entity, home was really the people that bring you peace,” writes Patvakanian.

Patvakanian recounts the everyday lives of the Lazaryan family with confidence and ease. This is how he describes Haso horqur as she calls out to her “sons” to come to the kitchen: “The two entered and sat at the table as Haso served them coffee. Closer up, Khatchik saw how the years of mourning and hard work had left their marks on Haso’s face. New wrinkles, dark circles around her eyes, and thinning short hair now replaced the once plump and smiling face of his dear Haso. She still had her heavy-set, full figure and was dressed practically but elegantly, donning her favorite black sweater vest and warm sweatpants.”

The ancestral traditions and values of the village come through, even if subtly: Khatchik’s cousin Evelina’s mother-in-law’s hearing was perfect, but she watched her soap opera at full blast “to remind everyone, particularly Evelina, that she was still in charge in that house.”

An important part of the plot is the relationship Khatchik starts with Siranoush, a childhood friend he had always had special affection for. Siranoush is now engaged to be married, yet the two secretly indulge in the “forbidden” — in what their “home and family values” did not condone. The relationship falls apart and so, it would seem, does the novel until Arevik, the young nurse who helps Khatchik recover from his injuries at the hospital in Kapan where he was brought when the newly constructed building at KapanKar collapses with him in it, comes to show the way.