By Nare Sukiasyan

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

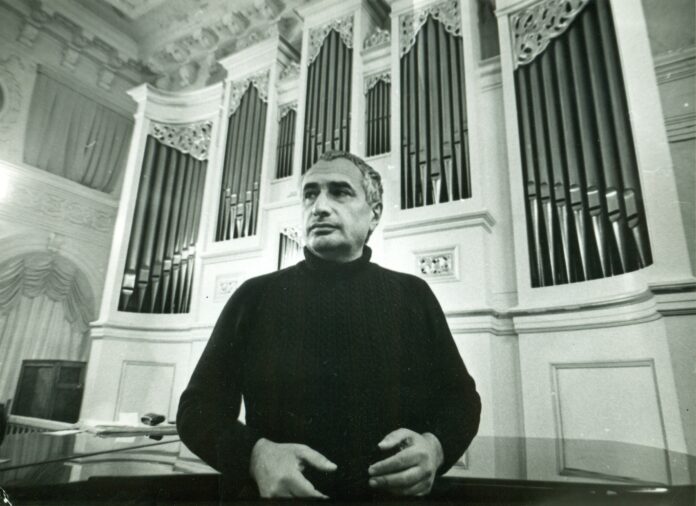

YEREVAN — Armenia is witnessing a sustained organ music revival, led by a community of professionals dedicated to preserving and expanding the country’s organ traditions. At the heart of this movement is the legacy of Vahagn Stamboltsyan, a renowned organist and teacher whose vision for creating a robust organ culture in Armenia is finally taking shape.

The sound of the organ that filled the hall of the Yerevan Komitas Chamber Music Hall last fall was unlike any concert that had taken place before; it was pure, ethereal, sacred and even mystical. Perhaps it was the tone of the newly restored organ. Or perhaps it was the sound of a dream come true: the dream of a man who had the courage to dream big.

Following that concert in an informal setting with Armenian organists and the festival organizers, I was moved by how this small community carries the responsibility of preserving Armenia’s organ tradition with passion, deep devotion, and love. Organist Tereza Voskanyan called the instrument “sacred,” describing the music of Bach and Komitas as “the highest form of musical expression.”

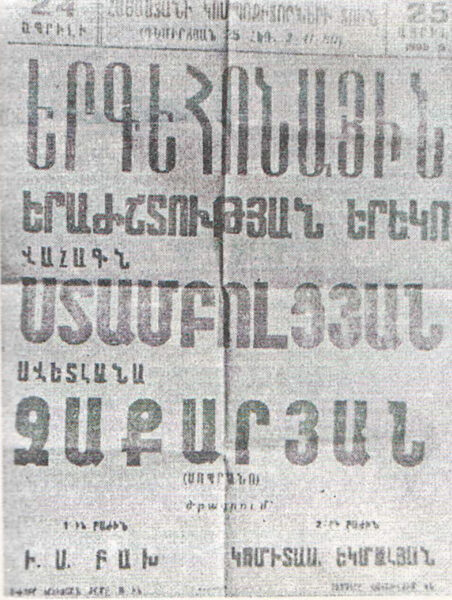

To understand the roots of this dedication, we must go back to the last century, when the instrument first entered the Armenian cultural sphere.