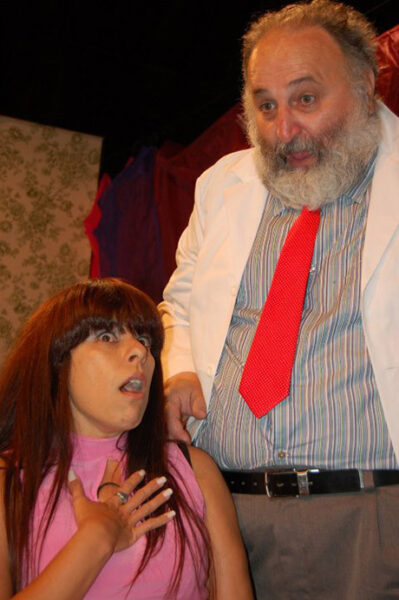

YEREVAN/GLENDALE – Aramazd Stepanian (born 1951, Abadan, Iran) is an Armenian theatre, film and television actor, producer, director, playwright, and translator. After graduating from Kooshesh-Davtian Armenian High School in Tehran, he moved to England, where he lived for 20 years. In London, he studied politics and drama at Thames Polytechnic (now the University of Greenwich), and completed courses in acting and stage directing. Between the years 1976 and 1989, Stepanian produced some 25 theatrical performances in both Armenian and English in London. He also founded a theatre there, Alperton Performing Arts Centre, staging plays in both languages for three years. In 1990, he relocated to California. Over the course of 35 years, he has staged at least 100 plays in English and Armenian. In 2006, he opened Luna Playhouse in Glendale, where he served as artistic director and producer. Luna Playhouse presented 12 different productions during its first year alone, more than some 60 productions, shows, concerts in total, establishing it as one of the most active theatres and performance arts centers in the area. He closed the theatre in 2011, as rising rents and more importantly the lack of any serious interest from other theatre and performing artists made continuation very costly and artistically unsatisfactory, as he was spending all his energy to cover the expenses rather than doing serious theatre work. Stepanian is the author of eight books published in both Armenian and English.

Aramazd, your creative biography is impressive. What would you say is your most remarkable achievement?

I just love the theatre (and the arts in general), especially the rehearsals, and the camaraderie that is created amongst people who maybe of very different character, so much so that you one would never associate with them outside of the rehearsals and performances, but you work harmoniously on your common love.

And I persevere (a trait I have inherited from my mother). And I initiate and take risks (my father). I have established two theatres in my life, one in London, one in Glendale. Neither survived, but I did it. I also led the team of Iranian Armenian students in Manchester, England, who cleared 150years of debris and damp of the cellar type space under the Armenian church and turned into a community center that has served the Armenians of Manchester for fifty years. I staged around 25 productions in London and at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. But in the 1970’s and 1980’s, the London community was small in numbers. And only a few thousand could be counted on to ever participate in any kind of Armenian cultural event. Fewer people meant fewer theatre practitioners. And none of the Armenian associations were interested in staging plays. I’d estimate that in the 15 years or so that I was active, there were maybe 4 or 5 other theatre plays staged in London.

If I have the means and the resources, and the people who want to work with me, I undertake major projects, I do a big production, or three big productions. In 2024 I staged three contemporary Armenian plays, in both the original Armenian and in English translation — six productions in total, rehearsed and staged in about ten weeks. If I don’t have the resources, the Armenian speaking actors, then I do three small scale plays with non-Armenians — in English. In 35 years in the US, I think there have only been two years, when I did not stage a play, and one was the Covid year, which I used to publish Armenian Playwrights Volume 1 and the Samad Behrangi book.

By the way, I’ve read your translation of The Little Black Fish by Behrangi. You intentionally used the Iranian-Armenian dialect. That same stylistic choice is evident in the title of your other translation, My Grandpa’s Journey by Gabrielle O’Sullivan. How justified is it, in your opinion, to use a specific dialect in literary translation?