BERLIN — Every April Germans join with Armenians to commemorate the victims of the 1915 Armenian Genocide, with prominent events in Berlin and Frankfurt organized by the Central Council of the Armenians in Germany (ZAD) and the Diocese of the Armenian Church in Germany.

This year, the 110th anniversary, several other cities hosted events, from Stuttgart to Bremen, Hamburg to Cologne and Munich. Jonathan Spangenberg, chairman of the board of the ZAD, opened the gatherings both in Berlin and Frankfurt, and Bishop Serovpé Isakhanyan, Primate of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Germany, offered concluding remarks and requiem prayers.

Cornelia Izakaya Seibeld, President of the Berlin Abgeordnetenhaus (parliament) and Dr. Bastian Bergerhoff, Frankfurt City Treasurer, greeted guests in the two venues, respectively.

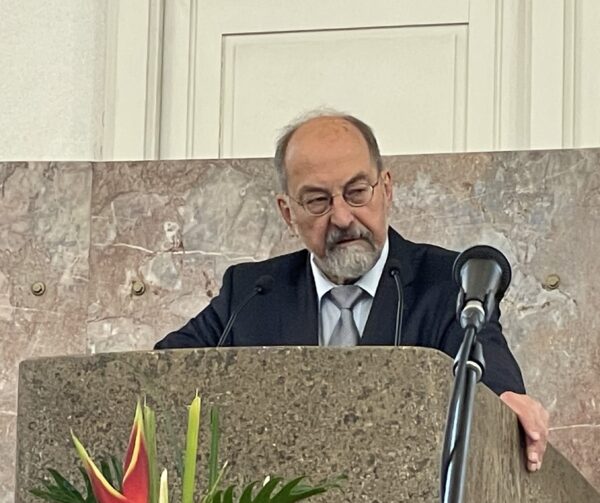

Guest speaker Cem Özdemir, agriculture minister of the outgoing federal government, addressed the gathering in the capital, and Dr. Otto Luchterhandt, legal scholar and professor emeritus, spoke in the St. Paul’s Church in Frankfurt. Luchterhandt provided an in-depth review of the juridical foundations for and history of anti-genocide legislation.

The German Role, Then and Now

“The genocide is also inextricably linked to Germany,” Spangenberg stated, setting the tone by focusing on the historical role Germany played at the time, and its moral, political consequences for the present.