By Hugh Morris

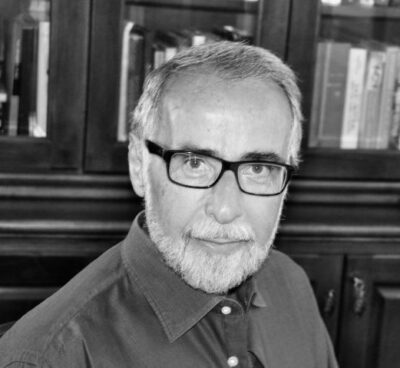

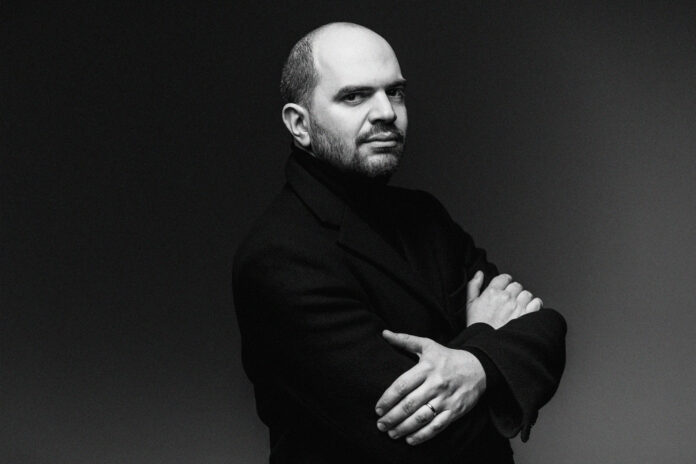

NEW YORK (New York Times) — Kirill Gerstein, a Soviet-born pianist whose parents sold their only proper asset — a garage — so that they could afford plane tickets to the United States for their son’s education, approaches music in a way that recalls something his countryman, the conductor Kirill Petrenko, once told him: “I sacrificed so much in my life to not do things by default.”

The career of Gerstein, 44, is filled with moments that defy a belief in doing things “by default.” There was the time when he devoted a significant portion of his $300,000 Gilmore Artist Award to commissioning new piano music from composers across jazz and classical music, placing Chick Corea and Brad Mehldau alongside Oliver Knussen and Alexander Goehr. Or there was the time, in 2017, when Gerstein championed a new, shockingly modest critical edition of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 rather than the grandiose, more recognizable version. Or when, as many streamed performances during the pandemic, he instead organized a series of free, online seminars that featured musicians alongside luminaries from the wider arts scene.

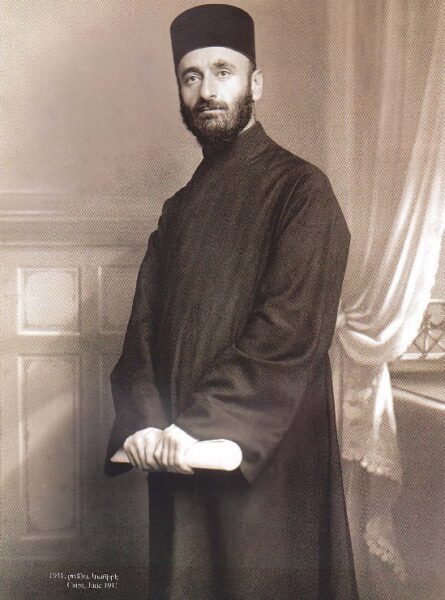

Now comes Gerstein’s latest project, “Music in Time of War,” a recording that is expansive in its program and packaging: a 141-minute double album of works by Claude Debussy and the Armenian composer and ethnomusicologist Komitas Vardapet, accompanied by a 174-page book of conversations, essays and photographs that situate the music deep in its historical context.

The album — which beyond solo piano pieces also includes works for piano and soprano (with Ruzan Mantashyan), and piano duo (with Katia Skanavi and Thomas Adès) — was released in mid-April. Its timing came at a poignant midpoint for both composers: March 25, the anniversary of Debussy’s death, and April 24, the date Armenia commemorates as the beginning of the 1915 genocide in which up to 1.5 million Armenians were killed by the Ottoman Empire. That led to post-traumatic stress disorder for Komitas, who while living in Constantinople (now Istanbul) was deported to Anatolia and brutalized by a guard before being released, then eventually suffered a nervous breakdown.