ALFRED, N.Y. — The Alfred Ceramic Art Museum at Alfred University will be host to an exhibit dedicated to sculptor Reuben Nakian through December 30.

Nakian (1897-1986) was born in Queens, NY, to Armenian immigrant parents. As a young man, Nakian could draw. His parents encouraged him. At the age of 12 he discovered New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Around that same time, he acquired a copy of Bulfinch’s Mythology, originally published in 1867. Greek myth became a touch stone. At 15, Nakian graduated from high school. He took a job in New York determined to find his way to being a professional artist. When he died at the age of 89, the New York Times acclaimed him as “one of the most distinguished American sculptors of the 20th Century” (New York Times obituary, 12/5/86).

Reuben Nakian is best known for his large-scale bronze sculptures. However, Nakian left for posterity a large, highly significant body work in the ceramic medium. It is this less recognized, but unquestionably important work the Alfred Ceramic Art Museum is celebrating with this current exhibition “Reuben Nakian: The Impassioned Gesture.” In a 1981 interview for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art speaking of ceramics Nakian remarked: “You don’t have to cast it. When you cast, things are lost. You put it in the kiln, and it has got the thumbprints. They are still there. It is a great medium.” Early in his career Nakian apprenticed with legendary sculptor Paul Manship, perhaps best known for his sculpture, “Prometheus,” at Rockefeller Center, New York City, who modeled with plasteline, a non-drying clay not suitable for firing. Nakian said: “Clay has got life. Plasteline is alright, but it is not life. Clay is the real thing.”

Nakian was a guest of honor at the “Famous Artists’ Evening” at the White House (1966), and the Smithsonian Institution produced a documentary on his life and work titled “Reuben Nakian: Apprentice to the Gods,” (1985). He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1931 and a Ford Foundation Fellowship in 1958, and he represented the Unites States as the major sculptor in the VI Biennale in Sao Paulo, Brazil (1961) and the 1968 Biennale in Venice, Italy. Nakian was known best for his monumental sculpture in bronze which are now part of the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Museum of Modern Art; the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution; the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. The list goes on and on to include 65 leading art museums in the US and internationally.

A word about myth from well-known authority on comparative religion Karen Armstrong. She writes in her 2005 book, A Short History of Myth: “Mythology is not an early attempt at history and does not claim that its tales are objective fact. Like a novel, an opera or a ballet, myth is make believe; it is a game that transfigures our fragmented, tragic world.” In another passage she writes: “Our modern alienation from myth is unprecedented. In the pre-modern world mythology was indispensable. It not only helped people to make sense of their lives but also revealed regions of the human mind that would otherwise have remained in accessible.”

Throughout art history artists have turned to mythology for its fundamental human themes, which serve as a means of philosophical inquiry. The stories of ancient Greek mythological figures have inspired Renaissance masters, modernist painters and sculptors and conceptual artists alike. Imagine Reuben Nakian as a young want-to-be artist avidly reading his copy of Bulfinch’s Mythology one day and visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art the next to see these myths come to life in paintings by legendary artists. For Nakian an indelible impression gave birth to a lifetime of creativity.

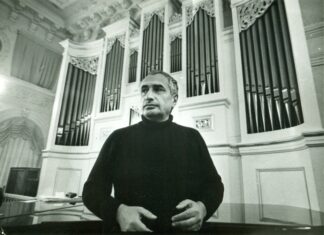

Collection of the Reuben Nakian estate, photo by Brian Oglesbee