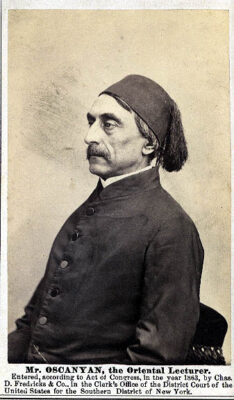

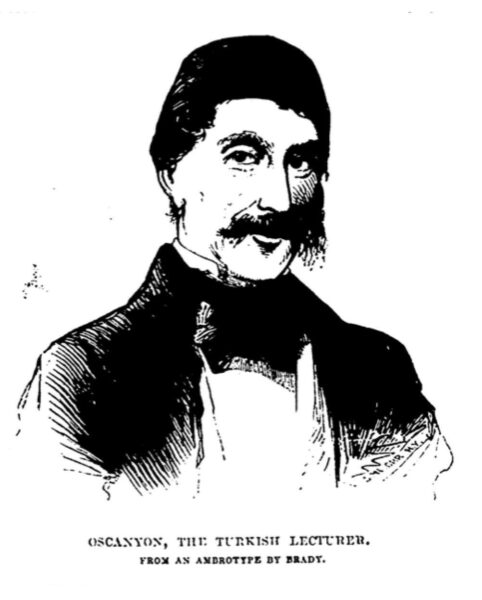

BELMONT, Mass. — Scholar Nora Lessersohn, in a recent lecture online at the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR), shed light on perhaps one of the earliest known Armenian Americans, Christopher Oscanyan.

Whether under the name of Khachadour Vosganian, Khachik Oskanian, or Christopher Oscanyan, this unique figure’s name has remained simply a name, with the majority of publications or articles merely noting his existence as the first of a string of Armenians who came to the US for their education, which later in the 1880s led to mass economic, political, and refugee immigration to the US, increased exponentially by the Hamidian Massacres of the 1890s and the Armenian Genocide of World War I.

Lessersohn’s research and her lecture aim to fill this void in the public’s knowledge of this highly interesting figure in Armenian-American community history.

Story of Ottoman Armenian In Changing Times

Lessersohn, a doctoral candidate in history at the University College, London, described her research as filling in the story of a man named Christopher Oscanyan and his work to connect the US and Turkey, and his creation and reshaping of an identity in order to do so. She stated that Oscanyan’s story answers the main questions which started her on her academic path, especially, the question of why Armenian-American identity looks the way it does.

Oscanyan was an Armenian born in 1818 in Constantinople. As Lessersohn, noted, the Ottoman Empire, which was multi-ethnic and multi-religious at the time, was referred to in the US simply as “Turkey” and its people were often referred to as “Turks” regardless of their actual ethnic or religious background.