YEREVAN / BERLIN –Silvina Der-Meguerditchian is a multidisciplinary artist. She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, lives and works in Berlin. Her artwork uses different mediums such as installation, video, sound, mix-media and performance. The burden of national identity, the role of minorities in society and the potential of a space “in between” are important topics in her artistic research. Der-Meguerditchian is also interested in the impact of migration in the urban texture and its consequences. Reconstruction of the past and the building of archives are a red thread in her work. Her projects were awarded by different international institutions, to name a few, the European Cultural Foundation, Kunstfonds Stiftung, the Sharjah Art Foundation and the Goethe Institut. In 2022 she was awarded with the Falkenrot Preis, the working fellowships for visual arts by the Senate Department for Culture of Berlin and the “in view” grant by the Gulbenkian Foundation.

Silvina has been working as art director of the Houshamadyan project (www.houshamadyan.org) a project to reconstruct ottoman Armenian town and village life since its inception in 2011.

From 2014 she cooperates with “Women mobilizing memory”, a group of artists, writers, museologists, social activists, and scholars of memory and memorialization, who focus on the political stakes and consequences of witnessing and testimony as responses to socially imposed vulnerability and historical trauma.

She participated in “Armenity”, the Pavilion awarded with the Golden Lion at the 56. Venice Bienniale for the best national participation. Her artistic work has been shown in many exhibitions around the world, including, among others, Germany, Italy, Greece, Argentina, USA and Turkey.

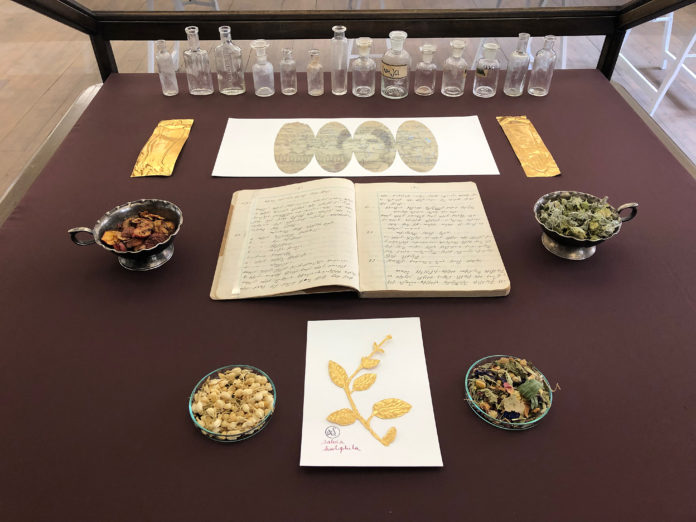

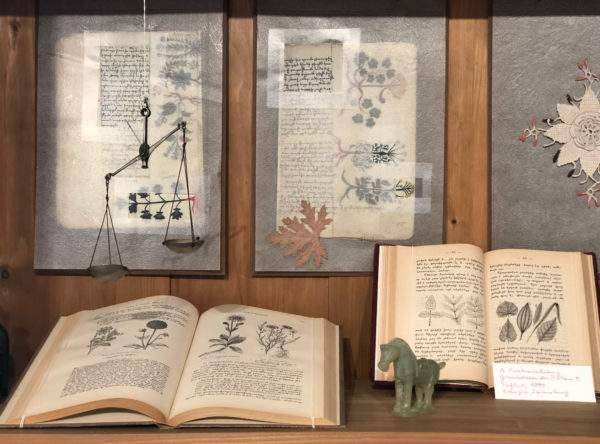

“Out of lost stories, things and objects Silvina arranges living archives, creates textures of memory which are material for new affiliations, open up spaces of action for a more hopeful future and a different kind of coexistence” (Barbara Höffer).

In 2021 Silvina Der-Meguerditchian: Fruitful Threads bilingual (German-English) catalogue was published by Verlag für Moderne Kunst, Vienna.