By Asya Darbinyan

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

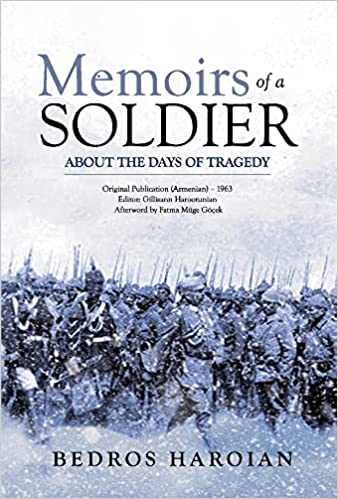

Bedros Haroian’s Memoirs of a Soldier about the Days of Tragedy (editor Gillisann Harootunian, Tadem Press, Fresno, CA, 2021) describes how Haroian, originally from the village of Tadem, served in the Ottoman army during the First World War, fought at the Caucasus battlefront and witnessed the Genocide. He survived torture in a Baku prison and joined the Armenian Legionnaires in Cilicia, only to be disheartened by the betrayal of the French and ultimately forced out of his homeland.

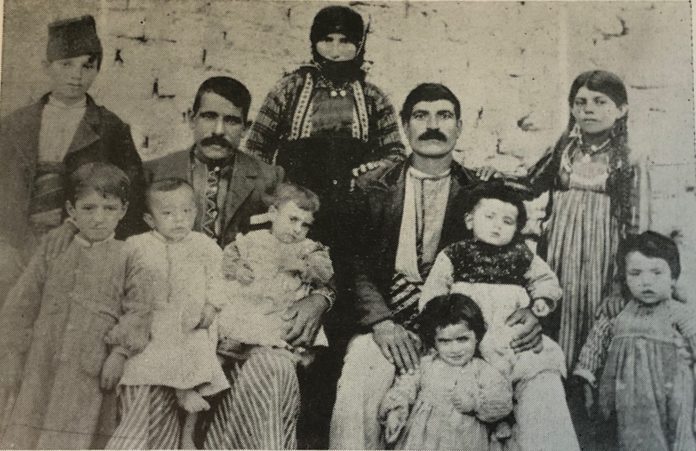

Haroian’s memoirs were first published in 1963 in Armenian. Now translated into English, this version includes a thorough introduction by the editor, photographs of Haroian, his family and loved ones, an afterword penned by Prof. Fatma Müge Göçek, as well as an extensive bibliography and notes that provide the necessary historic context to the specific events and multiple actors described in this fascinating testimonial.

Haroian’s account begins with the description of his home village of Tadem, in the Ottoman province of Mamuretulaziz (Kharpert). This chapter sets the tone for the entire memoir, showcasing Haroian’s immense admiration and love for his village and homeland: every church, sanctuary, school, mountain, gorge, neighborhood, garden, and well become part of the story. He makes certain to name all the family members, relatives, and neighbors he remembers, their professions and trades, including their past and the history of their struggle under the Ottoman discriminatory laws and practices. Similarly, at a later stage in his account, when his fellow “Tademtzi” soldiers fight and fall defending the lives of refugee survivors in the Caucasus and Cilicia, Haroian lists the “names of Tadem fighters” to honor them — the “heroic Armenian volunteers” (p. 307).

Growing up an orphan after the Hamidian massacres of 1894-96, Haroian managed to study four languages — Armenian, English, French, and Turkish — at the school built in Tadem by American emigres. These skills served him well throughout his life: when he traveled to the U.S. to join his brothers and work in factories of Lynn and Watertown, MA, when he served in the Ottoman army or was arrested in Baku, and eventually when working for the British army in Constantinople and negotiating with the French in Cilicia.