YEREVAN — “More than half a century passed after these days of deportation and killings, but they left an impression on my then-young mind in an indelible manner. It’s essential to render to history a few of those terrible events because of their general nature. And what is written here, believe me, are not stories collected from secondary sources, but events that I saw, heard, and lived.”

These are the words of Sargis M. Kasparian an Armenian from Gurin, Sepasdia (Sivas, in Turkish) born in 1906. Today, it is known as Gürün. After the Armenian Genocide, many of the Western Armenian city and town names became toponyms for villages in Armenia, often with the addition of Nor, or “new,” in front of the name. Nor Kyurin (Eastern Armenian transliteration) is one of those places.

Before the genocide, Armenians from Gurin — especially the men — began to immigrate to the United States for economic and security reasons. One of the many cities they settled in was Boston, where the local Armenians formed the Compatriotic Union of Gurin in 1899. It started as a student association, and briefly adopted the name Gurin Reconstruction Fellowship after World War I. During this time, the group was raising funds to construct the village of Nor Kyurin 15 kilometers south of Yerevan.

However, the name was not given to the land until after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1992. The origins of the village’s toponym are rooted in the survival of the Sargis, his brother Avetis, and his sister Tagouhi, and the unlikely encounter of Avetis with Hamazasp Sargsyan in 1976 — currently one of the oldest residents of Nor Kyurin and one of the leaders that helped name the village after the old town in Central Anatolia.

Sargsyan’s Documents

The municipality of Nor Kyurin does not know much about the village’s founding, other than having a government decision published in 1992 showing that the sovkhoz, or Soviet state farm, near Nor Kharpert village in the Massis region would become Nor Kyurin. This same document showed the name change of Leninakan to Gyumri.

The staff then brings Hamazasp Sargsyan, a resident of Nor Kyurin since 1969, to me to see what insight he can provide.

“I am the founder of this village,” claimed Sargsyan. The municipality employee near him scoffed and did not believe him.

At his home, Sargsyan displayed the documents in his possession. He had the governmental decree, decision, and a petition signed by the residents of Nor Kyurin declaring their wish to secede from Nor Kharpert and Marmarashen, as well as a letter from Avetis Kasparian, a doctor from Boston, who was the younger brother of Sargis.

The Kasparians Deported from Gurin

Together, Sargis, Avetis, and their sister Tagouhi had escaped the atrocities but had lost everything.

In Gurin, like many villages in the Ottoman Empire, the men were arrested first to prevent any revolts the Ottoman Army could not handle. Sargis’ father Manouk was one of these men.

However, Manouk was ill and he also had a Turkish friend who happened to be a high-ranking civil servant. He went with Sargis to the local prison and demanded the release of his friend.

Shortly after Sargis’ father was freed from prison, they sent Armenians from Gurin to the deserts by caravans. Except for Sargis’ ill father, there were no men on these caravans. Sargis realized that starvation, torture, and death were imminent.

“That day, the weather was pleasant, the sun shining, the vineyards and gardens were all green, all nature smelled like life and cheerfulness, but the Turkish state had decided to deprive us of our rights,” said Sargis.

Sargis’ caravan was moving slowly, moving about 15-20 miles within the last two days, when they stopped near a stream for the night. Once the light dimmed into dusk, Turkish bandits attacked the caravan, and Sargis’ father ordered him to bring their mules near him, only for him to be rushed by a bandit.

“I had barely reached one of our mules [when] I heard a gunshot and noticed that a Turk with a baton was advancing in my direction. I immediately ran back and dove in the stream and hid under reeds. I stayed there for four to five hours. From where I hid I could hear the cries and entreaties of Armenian girls and women, addressed at the Turks kidnapping them. Transfixed, I was afraid to move and say a word. My head was full of all sorts of terrifying images.”

Realizing the caravan’s guards were not preventing the bandits from pillaging the Armenians, many decided to escape back to their initial stop in Elbistan.

The caravan stayed there for 2-3 weeks, and Sargis’ ill father died and was buried there, unable to endure the mental and physical tortures.

Trying to speed up the process of the deportations and exterminations, the guards rushed the caravans into the Arabian deserts and did not allow the Turkish bandits to rob the Armenians for this exact reason. There was nothing more to rob, anyway.

Sargis and his family eventually reached Arel, 15 miles away from Aintab, with the caravan. This is where Sargis’ mother Nazeli died and they are unaware of what happened to her body.

“That night a few times, in her delirium due to fever, she advised me to do good things, cure patients, and take care of them…It looked like she had in mind my father’s plan of sending me to Beirut to study medicine. It was strange that, after so many ill-treatments by the Turks, she did not urge revenge on me, or to seek blood against blood, but instead, she recommended education and good acts.”

From that point on, nine-year-old Sargis, his seven-year-old brother Avetis, and three-year-old sister Tagouhi were on their own.

Sargsyan Meets Avetis

In 1980, Dr. Avetis Gasparyan visited Armenia. He was aware of villages being named after some cities in Anatolia, such as Nor Kharpert. He was also aware that some Armenians from Gurin had been living in Armenia for quite some time now, so he wanted to visit.

He met with a friend in Nor Kharpert, and his friend wanted to welcome him properly with a good meal so he asked a friend, Hamazasp Sargsyan.

Sargsyan took them both out to eat and that is when he learned about Gurin.

“He told me about the history of Gurin and then left,” Sargsyan said.

It was after he met with Avetis that he became interested in the history of Gurin and learned a Compatriotic Union of Gurin of Boston had been formed in 1899, in which Avetis and Sargis were both members at one point. He also learned that since 1936, the Union’s goal had been to name a city in Armenia “Nor Kyurin,” but all their requests were turned down by the Soviet government.

Information about the Union is kept in an archive in Boston, and the information about the group has been compiled by Luc Vartan Baronian, Associate Professor of Linguistics at the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi – whose grandfather was also from Gurin.

The Union had periodicals from 1930-1933 called Gurini Housh, and they were also later published from 1976-1981 under the title Gurini Housher.

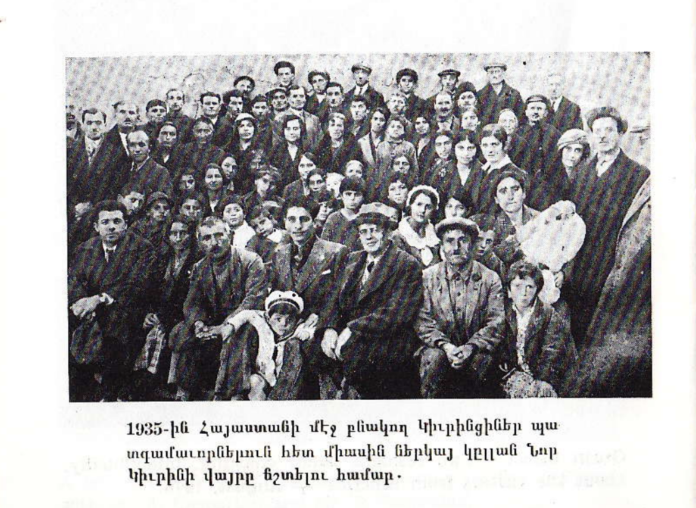

According to the Union’s 1936 Constitution and by-laws, in 1935 they had raised $5,000 for the construction of the village, and some of the members visited Armenia to sort out problems of obtaining land. This was sent as a formal request to the Armenian Relief Committee (ARC), which consented to the Union’s request to use the $5,000 to build five homes on a street named Kyurin in Nor Kharpert, and they promised it would double the number to 10 by 1936.

The Union then launched a campaign to raise $15,000.

Sargsyan said he publicized this information with a radio program he had, which would broadcast to the diaspora in 30-minute sessions, twice a week. He said he wanted to let the diaspora know about the story of Gurin and the desire Gurin Armenians had to create a Nor Kyurin.

The immortalization of their city was an approach adopted by many Armenians after the genocide to pay tribute to their beleaguered homes.

Return to Gurin

After the death of their mother, Sargis and his siblings were transferred by village police to the local station and stayed in Arel at the home of Khaliloghlu Mehmet Kahya. They stayed there as shepherds until the beginning of 1919, when his cousin Vartan found them and took them to Ayntab.

The armistice period had begun in the spring and therefore Sargis, his siblings, and some friends decided to visit Gurin using the route of Marash and Elbistan. Sargis recalls standing on top of the hill and seeing his town destroyed and in an unrecognizable state.

“We contemplated the quarters, streets, houses, the river that was familiar to us, from Shoughoul to Tsakhtsor. The beautiful town of gardens, Gurin, which used to smile with an invigorating mellowness, like a huge bunch of flowers, with its fruit trees in blossom, during this awakening season of spring, had ceased to exist. The old, joyful, and beautiful Gurin did not exist anymore,” Sargis said.

Before the war, 28,000 Armenians lived in Gurin and by 1921 there were none left, according to the Armenian-language book The History of Gurin.

Sargis eventually found his home in Gurin, but it was occupied by a Turkish woman from Kemakh with her two children. He told her that it was his house and wanted her to leave. She eventually agreed. Sargis explains how during this time, some Turks tried to win over the hearts of Armenians and he thought he knew the reason why.

“The reason for that was not the willingness to expiate the crimes they had committed, or to ease their consciences, but simply to lessen and avoid the punishment that they thought was going to be inflicted to them by the Allied forces,” said Sargis.

After witnessing the destruction of their hometown and people, the Kasparians and many other Armenians from Gurin fought to keep the memory of their town alive.

The Union’s Mission and the Kasparians’ Role

The Kasparian family was torn apart due to the Genocide, but this did not stop Sargis and his siblings from finding their way in a world that had just taken everything from them.

According to the first issue of Gurini Housh, Sargis traveled from Greece to study in Boston, where the Union was founded. It is not clear what he studied or worked on, but was monetarily successful given the hundreds of thousands his brother Avetis and him donated to the Armenian General Benevolent Union in Armenia, according to a letter from Avetis.

It is unclear what happened to his sister Tagouhi, but Baronian believes he has a documented border crossing going into Canada. The name of the woman was Tagouhi Casparian Sohigian, and she crossed into Canada at age 35 in 1950.

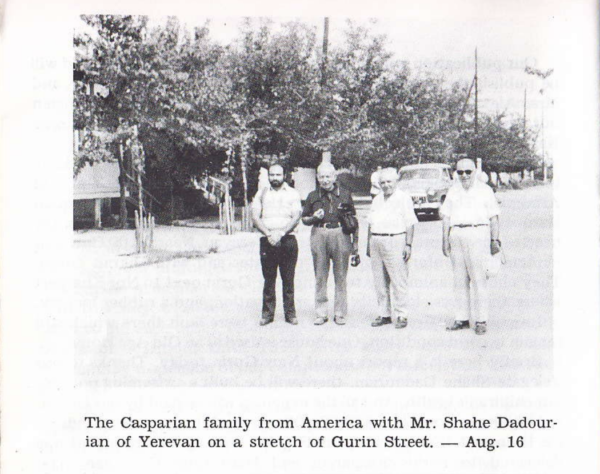

Avetis completed medical school in Milan in 1936 and traveled all over the world. He and his brother Sargis would become heavily involved in the Union, and would eventually make a trip to Armenia, which is documented in the 1976 introductory issue of Gurini Housher.

The brothers can be seen walking around Gurin Street in Nor Kharpert. Until that time, the Union had sent over $80,000 worth of electronics to Armenia. According to Gurini Housh, Sargis Kasparian and Harootyun Chooljian were tasked with funding and sending the equipment.

This is when Avetis met Hamazasp Sargsyan, a local living in the Nor Kharpert sovkhoz, who has been there since 1969.

As mentioned before Avetis told Sargsyan about Gurin when they were out to eat, so the memories of Gurin and Avetis stuck with him since the village’s founding.

Years later, in 1991, the Soviet Union was collapsing and Armenia was at war with Azerbaijan over the sovereignty of Nagorno Karabakh, and many villages were beginning to change their toponyms.

Sargsyan and his brother led their sovkhoz to petition for their own village and name. On February 18, 1991, the petition which contained the signatures from the residents of the sovkhoz was recognized.

Then on November 14, 1991, the Supreme Council of Armenia signed a decree, stating that the sovkhoz near Nor Kharpert would be on the list of settlements of Armenia and it would form its village council.

Finally, on March 13, 1992, the Supreme Council of Armenia signed the decision to give the former sovkhoz the name of Nor Kyurin.

Sargsyan claims his influence and petition helped rename the village into Nor Kyurin and says he was the president of the Union of Nor Kyurin at the time.

At the time, Avetis was still in Boston, and he presumably did not hear about the decision of the Supreme Council because he sent a letter on August 27, 1992 to the Prime Minister Gagik Harutyunyan, a copy of which Sargsyan had. In his letter, he explained how he has fulfilled his duties as a doctor and as an Armenian doctor. He mentions donating hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Armenian General Benevolent Union in Yerevan, along with his brother Sargis. He also mentions how Sargis passed away on December 24, 1987, from a heart attack. He did not get to see the village be named after his hometown.

He ends his letter with one final request: “I would like to plead for you to give the local people of Gurin land in the city. Thank you very much,” Avetis said.

A little under a year later Sargsyan wrote a letter to Avetis, wanting to share with him the news and updates on the village. At the time, there were about 800 residents, many refugees from Sumgait and Baku.

“The new leaders of the Republic cannot help us, but we are making no demands,” Sargsyan said. “Nor Kyurin was just founded at a bad time.”

He continues to describe the condition of the village, mentioning how it does not have a school, administrative building, or doctor’s office yet.

Life did and does continue for the people of Nor Kyurin despite three wars and emigration.

The Compatriotic Union of Gurin and Sargis and Avetis achieved their ambition. The Western Armenian town’s name is memorialized and will serve as a reminder for the Gurin Armenian blood spilled during the Genocide. Although the Gurini Housh periodical is no longer in circulation, the memories of Gurin live on.