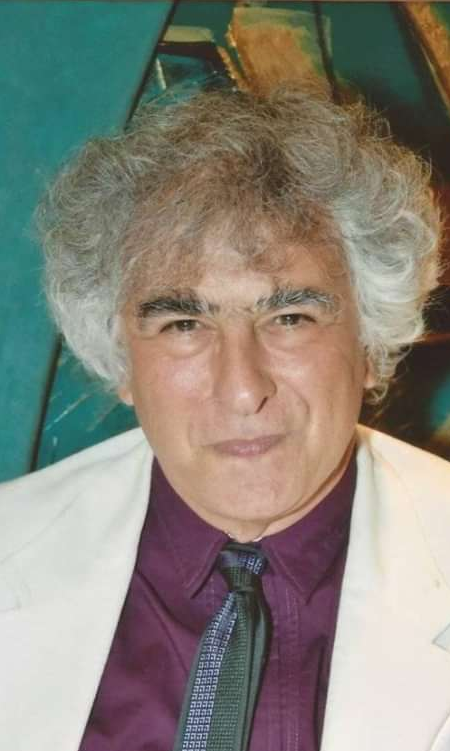

YEREVAN/BUENOS AIRES — Argentinian-Armenian composer, musicologist, writer, translator, and artist, professor Juan Yelanguezian was born in 1950 in Buenos Aires. In 1972-1973 he studied journalism at the Catholic Institute of Social Studies; in 1974-1975, stage Philology at the University of Yerevan; in 1982 he graduated from the Catholic University of Argentina (history of music, plastic arts and literature), in 1984 from the Department of Musicology of the Yerevan State Komitas Conservatory, in 2001 from the Composition Department and in 2004 with a PhD of the same Conservatory. He has been a professor at the Institute of Culture of the Catholic University of Argentina and in the University of Buenos Aires at present with the course “Armenian Civilization and Its Influence in the Occident.” He is a member of the Writers’ and Composers Union of Armenia. His biography is included in specialized books in his country, foreign countries and in the National Encyclopaedia of Armenia.

His musical compositions have been performed in Buenos Aires, Yerevan, Paris and elsewhere. Yelanguezian has composed symphonic and chamber works: Hetanós Idololatris (Pagan 1974, cello piece), Catharsis (1977, for piano and actors), From my Ancestors (1981 plastic, poetic and musical performance) Adolescence Songs (1981), Songs of Fading Lights (1981) Dialogues (1983, Trio), Madagh (1983, strings quartet), Songs of Fading Lights (1983), Aquarelles (1983, piano) Arean Suite (1991), From the Blood Suite or Cycles, dedicated to the victims of the Artsakh war, for piano, Thraki (1993, Fugue for violin and violoncello), Armenian Gods or Vahagn’s Room (2001, Symphonic poem), Mission (2004, Flute and Strings Orchestra), etc.

He has published literary works in Spanish: Anthology of Armenian Poetry (1984), Arian, Poetic Anthology (1994), Armenian Culture, Science and Tradition (2001), Esmirna, 1922…The Dr. Hatcherian diary by Dora Sakayan (Montreal 2001, translation), Zim Kilikia (2011), and others. He has published his musicology researches into the many academics magazines in the world. His musical, literary and painters works have been awarded and distinguished with a number of very important prizes in Argentina and Armenia. He is the author of the Orphans of Armenia, Angels of Heaven mural at the Saint Paul Armenian Church in Buenos Aires homage to the centenary of Armenian Genocide (2014-2015). Dr. Yelanguezian was the only guest from Argentina to present his dissertation at the 4th National Congress of Western Armenians in Paris, in 2015.

Juan, a brief acquaintance with your biography shows how your Armenian heritage is present in all three of your professions — music, literature and painting. Being a third-generation Argentinean Armenian, how have you managed to keep your Armenian identity so vivid?

Well, it is a question that is always asked me, but the prejudices of society indicate that you will be nothing if you do not dedicate yourself to one of the talents you inherited and professionally train by your own decision.

The truth is that in order to create, I need to go from one art or trade to another, at the creative moment. I write poetry that takes me to music and then to art or in different orders.