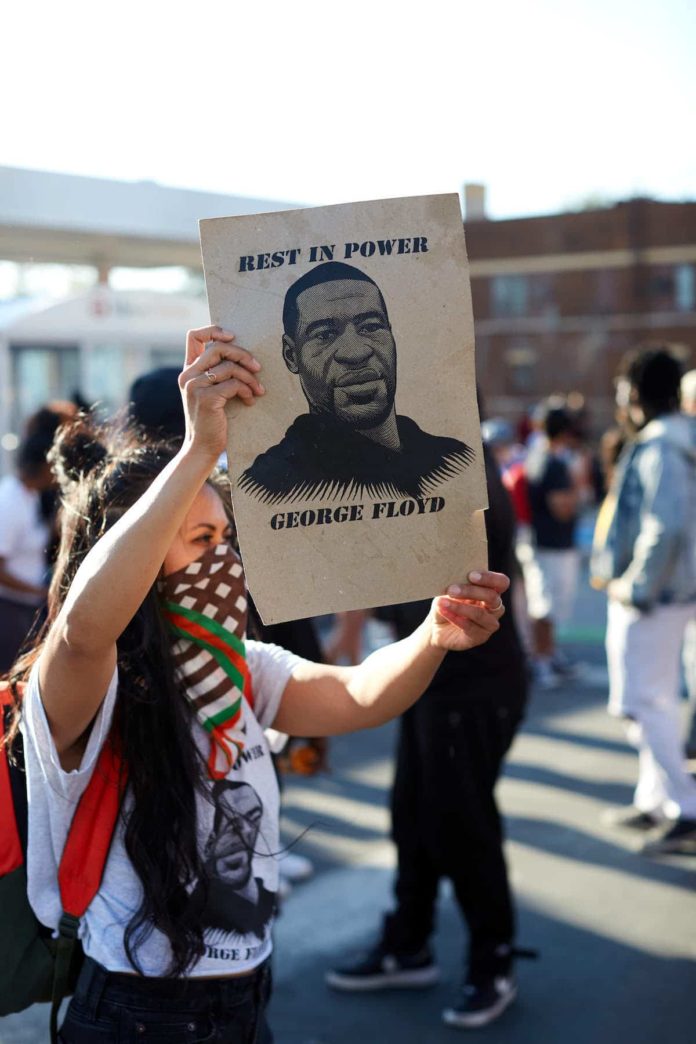

MINNEAPOLIS (mymodernmet.com) — For Dr. Artyom Tonoyan, the need to be politically active started at a young age. Growing up in Soviet Armenia, he saw firsthand how protests could bring a wave of change. So as an avid photographer, it only made sense for him to hit the streets as protests against the police brutality that resulted in the murder of George Floyd took hold across Minneapolis and St. Paul.

His photography is an incredible documentation of this critical moment in American history. Tonoyan spent time at the site of Floyd’s murder where a mural has been transformed into a memorial and then ventured to St. Paul, where grief boiled into frustration. His images of protestors (young and old) holding their signs, while simultaneously mourning Floyd and all that his death represents, share the somber yet peaceful side as well as the rage and responding violence.

Buildings were burned, police officers arrived on the scene, and teargas was released on the protestors — Tonoyan included. For Tonoyan, who is a research associate at the University of Minnesota’s Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, being present was important in order to make sure that the public could have a true visual of what was happening.

We had the opportunity to speak with Tonoyan, who has previously documented the fallout from Philando Castile’s killing in nearby St. Anthony, about his motivation for photographing these events and what he saw while in the middle of the protests. Read on for My Modern Met’s exclusive interview.

First off, how are you feeling? I know the atmosphere must be tense.