By Tigrane Yegavian

The famous French-Armenian historian Anahide Ter Minassian did not have the chance to see this newly published book she translated from Armenian to French in the twilight of her life. An iconoclastic story, Vahé Oshagan’s short novel Odzum [anointing, or unction] (Vahé Ochagan, Onction, Marseille: Editions Parenthèses, 2020, 128 pages, 19 euros.) [https://www.editionsparentheses.com/Onction] is one of the most relevant stories in the book Tagarti shurch [around the trap] published in New York in 1988. This committed and fiercely free text questions the engagement, action and revolt of a whole generation, the one which turned twenty at the end of the 1970s.

What have been the attempts of Armenian literature to respond to the challenge of armed struggle? This article was written in part based on an interview that the late historian had given us about Vahé Oshagan, shortly before her death.

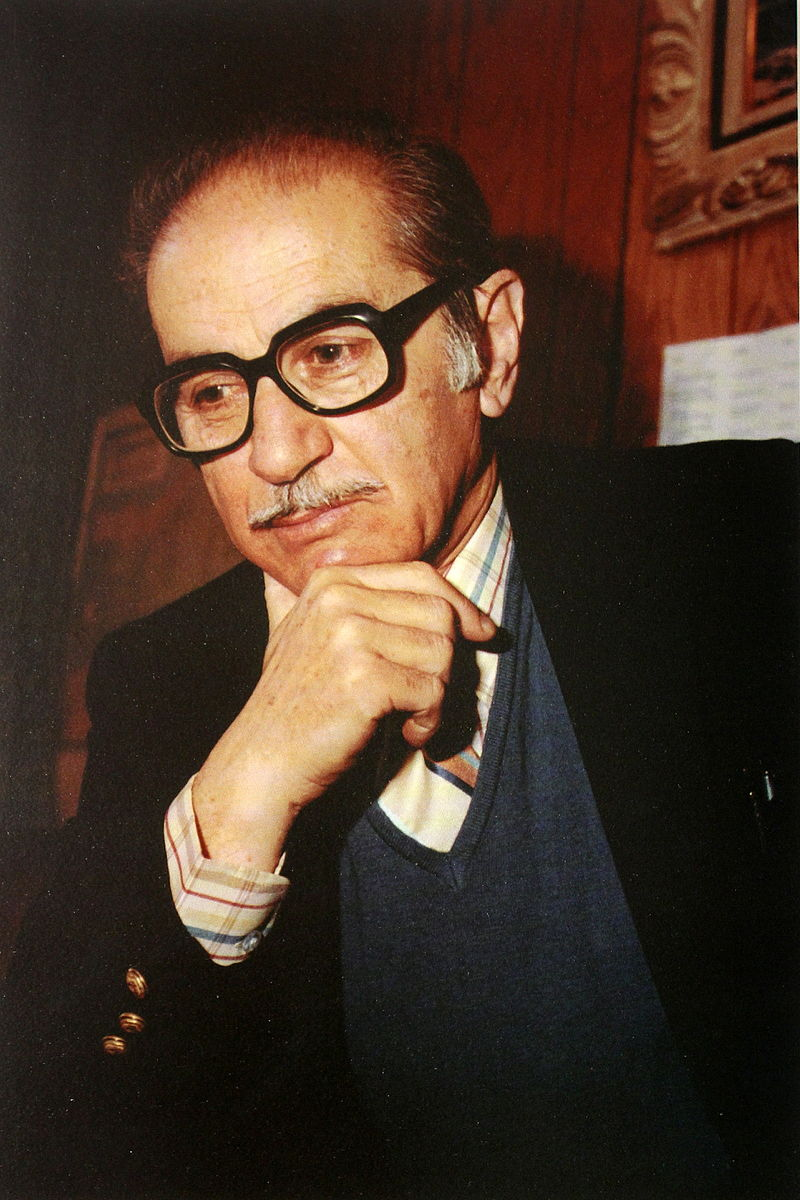

A “transgressive novel,” if there are any, Unction evokes an episode of Armenian life in the diaspora scarcely or poorly addressed in our contemporary literature. Let’s call this genre “Hay Tad-ism,” because it’s about armed struggle. In contemporary Western Armenian literature, there are some authors in the diaspora who have taken up this subject. Among the most committed, one can find three writers from the second half of the 20th century, two of whom fell into oblivion: Raymond Boghos Kupelian and Kevork Adjemian (who was one of the founders of the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia [ASALA]); but also Vahé Oshagan (1922-2000). Of these three names, only Vahé Oshagan is relatively accessible to us, as evidenced by the recent publication in Armenia of his poetic work (Gayanner [stages], Erevan: Khachentz, 2017).

A minor genre, if any, this literature is currently almost exclusively available in the Armenian language, apart from two novels by Kevork Adjemian which are about ASALA seen from the inside (A Time for Terror (1997) and Ruling over the Ruins (1999)). Literarily poor, it does not shine through style or aesthetics, but through its iconoclastic and transgressive dimension.

Attracted by existentialism when he frequented the Sorbonne and the cafes of Paris in the 1950s, he had maintained all his life a kind of great gap between his membership of the ARF Dachnaktsutiun, and his loyalty towards the Armenian community structures, and on the other hand, a transgressive writing, a yearn to awaken a whole people from its inertia. If at times he developed a “poetry of the absurd,” he nonetheless remained faithful to a quest for meaning; a questioning of traditional standards, their exploration of the Armenian diasporic reality and its taboos. His poetry as well as his prose render in him a metapolitical project: it’s a question of breaking myths. But to replace them with what? And to pretend to what type of normality to suppose that this is the supreme aspiration of this revolutionary militant youth?