By Aram Arkun

Mirror-Spectator Staff

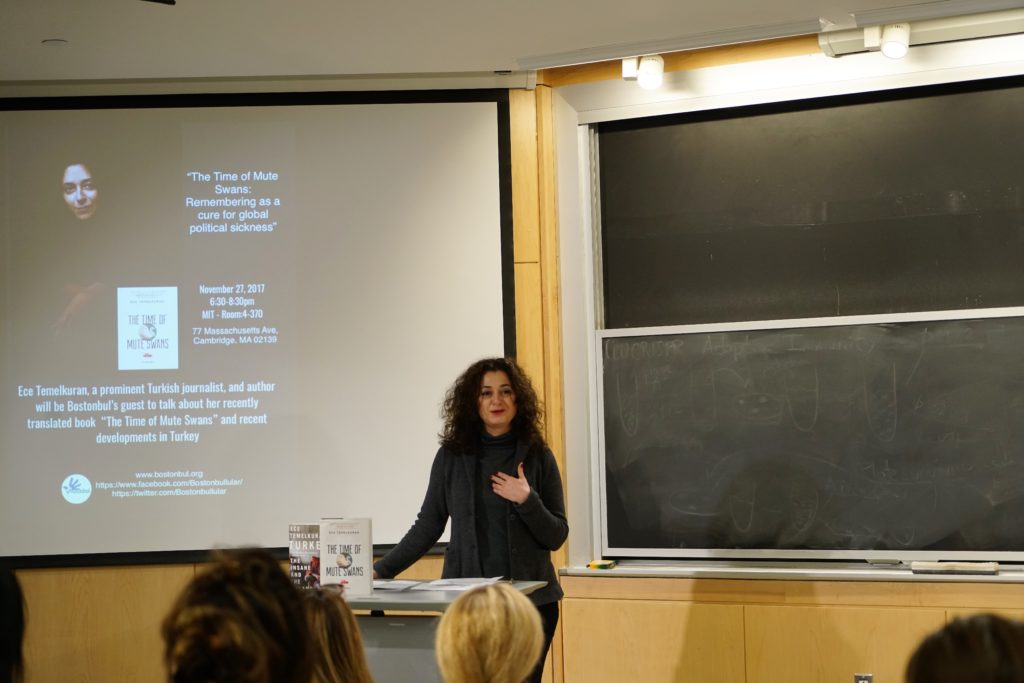

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Turkish journalist and author Ece Temelkuran presented a talk organized by the BostonBul organization at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on November 27. This event was part of the tour for the newly published English translation of her book, The Time of Mute Swans.

Temelkuran said that though this was a novel, it was at the same time a political work, so she would also speak about current Turkish politics.