Mirror-Spectator Staff

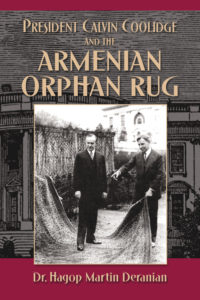

WORCESTER — The Armenian Cultural Foundation’s recent publication, President Calvin Coolidge and the Armenian Orphan Rug, sheds light on a little-known piece of American history. It also currently stands at the center of a political debate surrounding the White House’s refusal to release the rug featured in the book for an exhibit and book launch at the Smithsonian. However, for the book’s author, Dr. Hagop Martin Deranian, the work represents another chapter in a son’s lifelong journey to honor the memory of his mother and her battle to survive the Armenian Genocide.

At age 91, Deranian has seen much of the world and has accomplished much, too. He is a renowned dentist and has served on the faculty of Tufts University School of Dentistry. Deranian has written multiple books on Armenian subjects, including Worcester Is America, the Story of Worcester’s Armenians and Miracle Man on the Western Front: Dr. Varaztad H. Kazanjian, Pioneer Plastic Surgeon.

In 1929, his mother, Varter Bogigian Deranian, 44, died while visiting relatives in Providence. “I was 6-years-old when she died. I have spent the rest of my life in an attempt to accurately trace her story,” he said.

The younger Deranian was born in 1922 and grew up in Worcester. He attended Clark University in 1941, a few weeks before Pearl Harbor and served in the US Navy. He recalled taking an interest in Armenian history early on. “I wrote my first term paper on the Armenians. I didn’t get a good grade on it,” he chuckled, “but it tempted my imagination from there.”