By Edmond Y. Azadian

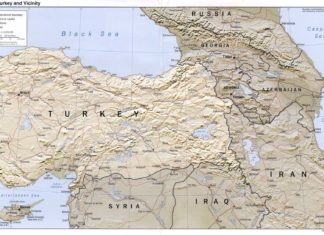

Small nations on the periphery of larger powers or empires benefit and survive when two major countries are in opposition or in competition. Armenia was able to manage its international relations, as long as Moscow opposed Turkey. Now that Russia and Turkey are mending fences, will that be at the expense of Armenia?

In Armenia’s strategic calculations, the Russian army base on its territory has only one significance: to defend Armenia against Turkey in case of a war or threat of a war. The Russian side may also have other objectives in projecting its power in the Caucasus region — objectives that are not germane to Armenia’s national interests, but they have been accommodated for the benefit of the larger good, meaning protection against a potential Turkish threat.

Since Vladimir Putin’s peace initiative, Russo-Turkish relations have been improving and a with a recent visit by President Dmitry Medvedev, they have reached an ultimate level, especially in trade and economic ties. It is predicted that very soon trade between the countries will hit the mark of $100 billion, making Russia one ofTurkey’s major trading partners. During Medvedev’s visit, 20 agreements were signed strengthening trade and economic ties between the two countries. Although outwardly benign, these

agreements have some strategic significance for Armenia. For example, one of the agreements relates to a nuclear power plant to be built by Russia in Turkey. This is in direct competition with Armenia’s nuclear plant through which Armenia was expecting to sell electricity to Turkey. Armenia’s Medzamor plant will be decommissioned by 2016 and a new one will be built, financed by foreign investment. Turkey’s competing plant may jeopardize Armenia’s prospects to replace its aging nuclear plant or in the best-case scenario, Armenia will not only lose an important customer for energy

export and, even more difficult, will have a competitor across the border.

This is a drawback on the business front for Armenia. Yet parties have also talked about Armenian-Turkish relations, suspended protocols and opening of the border between Armenia and Turkey.

Here, Medvedev’s pronouncements are extremely neutral and they don’t reflect at all the commitment of a strategic partner. “Russia and Turkey are interested in developing and consolidating stability in the Caucasus region, including the resolution of the Karabagh conflict. Russia, for its part, is determined to do its best to move ahead that process, utilizing all its means and its political clout,” said the Russian president.