Ashot Haykazun Grigoryan, author of the recently-published Christian Armenian Architecture and the Influence of the Pre-Christian Culture (Zangak, 2023), defines architecture as the art of building as only symbols can do. More than construction materials, the purpose of the structure, the consideration of surroundings, or any other consideration, avers Grigoryan, symbols characterize our architecture. The epigraph by fifth-century B.C. Chinese philosopher Confucius — “The world is governed by signs and symbols, not by laws nor words” — roots the book in the deeper significance of things that only symbols can reveal.

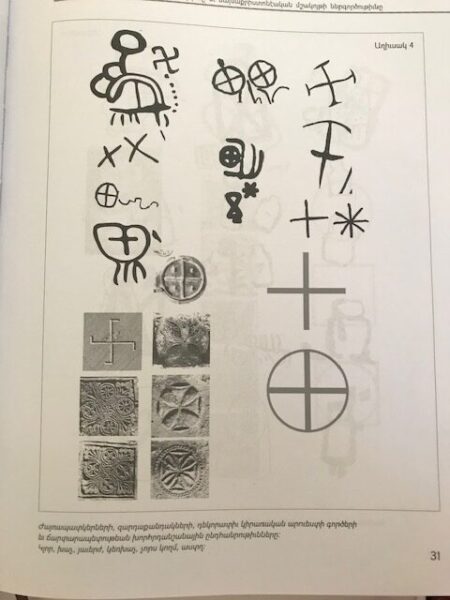

With his meticulously-researched 438-page study full of charts, illustrations and photographs of structures and monuments built from pre-Christian times through the late Middle Ages, both in the Armenian Highlands and urban centers, Grigoryan provides evidence for the symbolic foundation of Armenian architecture.

Symbols have played a key role in the creation of our pre-Christian culture and have left an indelible footprint on Christian Armenian architecture, posits Grigoryan. Interpreting Christian architecture from a symbolic perspective will reveal the continuity of the paradigm, he affirms.

There is much evidence of symbolic thinking in the first art of our ancestors, the rock carvings found in the Armenian Highlands, where whole histories are drawn as symbols. Symbolic images — such as the Armenian eternity symbol, the two interlaced triangles used in the art of cross stones, the tree of life that is widely used in structures of worship, the sun-lion, and many more — have been used repeatedly in our dwellings, places of worship and monuments. Even as they have evolved, adjusting to the needs of a particular place or time, the symbols have preserved their initial form and meaning, notes Grigoryan.

At least for the layman, Armenian architecture has been equated, almost exclusively, with the beauty and the magnificence of our churches, starting with Echmiadzin Cathedral, the mother church built in the fourth and fifth centuries following the adoption of Christianity by Armenia as a state religion in A.D. 301, the seventh-century St. Hripsime, one of the oldest surviving churches in the country, and the many others built in the Middle Ages and later. The unmatched visual appeal of the architectural designs of these churches is undeniable.

Grigoryan’s is simply an invitation to a new way of thinking that takes Armenian architecture beyond the Christian-pagan divide and expands it, giving it a wider, richer significance.