SAN FRANCISCO — For many of us, delving into history is interesting, but when that history involves a family member, it is that much more intimate as well as intimidating.

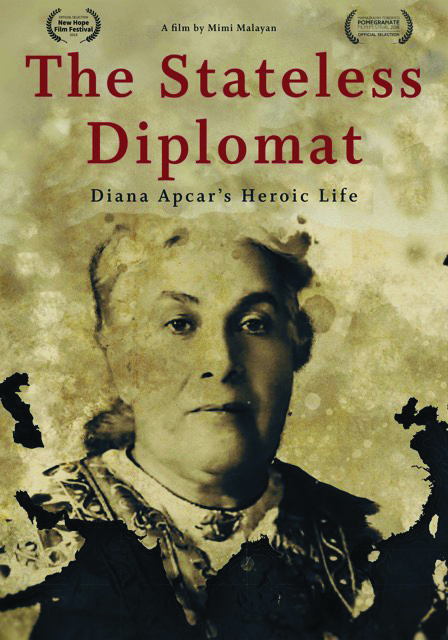

Mimi Malayan, the great-granddaughter of Diana Apgar, has made a film about her famous relative, which she hopes will restore her rightful place in history as a faithful servant of the Armenian people as well as a trailblazing diplomat.

Malayan’s documentary, “The Stateless Diplomat: Diana Apcar’s Life,” brings attention to the countless selfless gestures of Apcar during her fascinating lifetime which coincided with many historic events, including the Armenian Genocide, World War I, the Bolshevik revolution in Russia and the creation of an independent Armenia.

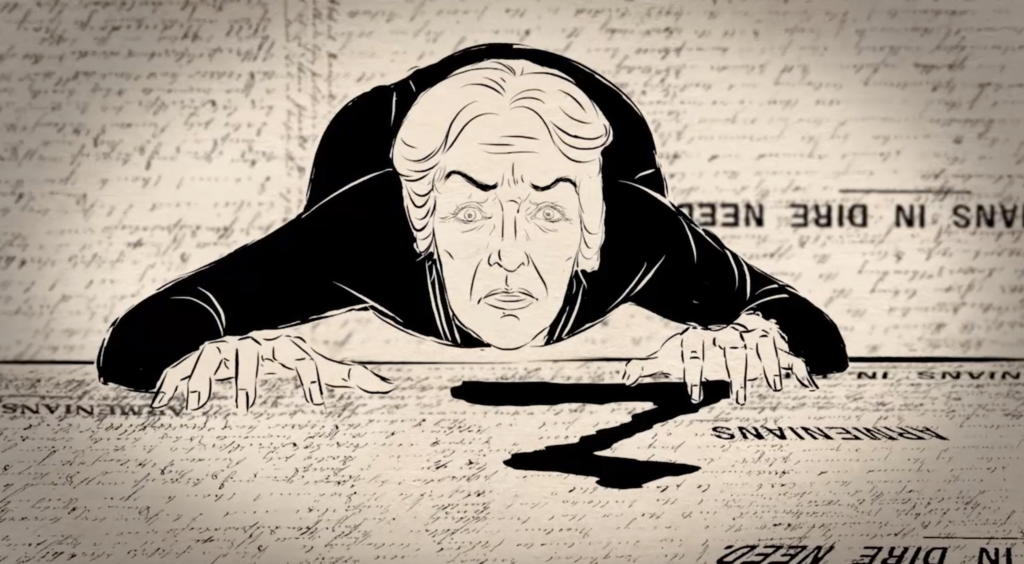

Connecting with her great-grandmother’s legacy humbled Malayan. The filmmaker said she had not realized the full range of her great-grandmother’s efforts to help refugees of the Armenian Genocide.

“The depth of her commitment and energy were overwhelming. She committed her life to his cause, helping Armenians however she could,” Malayan said.

In addition, she said, later as an ambassador for the First Republic in Japan, Apcar served a government whose legacy was not embraced by Soviet historians.