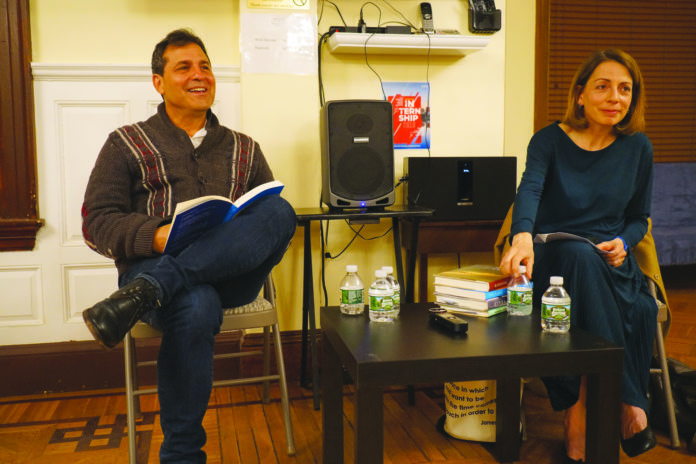

WATERTOWN – The Tekeyan Cultural Association (TCA) Boston Chapter and the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) New England District presented a literary evening on May 15 with California novelist Aris Janigian and Susan Barba, poet and editor, as discussant.

TCA Executive Director Aram Arkun thanked the AGBU and its local chairman Ara Balikian, traveling that week, for cosponsoring the event and introduced the new chairwoman of the TCA Greater Boston Chapter, Dr. Aida Yavshayan, who presented the biographies of the two speakers.

Janigian started the evening with a reading from his third novel, This Angelic Land. To make it accessible, he first provided some context. He explained that he chose as the most appropriate character to witness the destruction of the Los Angeles riots of 1992 a refugee from violence of the Beirut Civil War, Adam Derderian. The other main characters also are Middle Eastern. One of them is the Kurd, the best friend of Adam and a painter. Adam’s brother Eric, a documentary filmmaker, comes to Los Angeles to figure out what happened to Adam and speaks with the Wizard, an old Jewish mentor of Adam.

Barba said that this novel forms a bridge between Janigian’s heart-wrenching first two novels, Bloodvine, about two American-born Armenian half-brothers torn apart over a disagreement about a plot of land in 1950s Fresno, and Riverbig, the sequel, and his later works. They focus on the first-and second-generation Armenians in the US, whereas This Angelic Land moves forward 30 years or so.

In 1992, Janigian explained, he was living in Los Angeles, 32-years-old, in the mid-Wilshire area when the riots started. He said he had written three novels before his first published novel. He was working on a new novel when the riots happened but dropped that to work on this new topic and write his observations. However, Janigian said, “It was so complicated, the feelings I had watching the city go up in flames. Essentially I put the story aside for 18 years.” When the 20th anniversary of the riots were coming up he thought to revisit it and got advice from Arno Yeretzian of Abril Bookstore, who suggested making the main character Lebanese. That gave so many parallels (Lebanon and Los Angeles, the old world and the new, the Armenian Genocide) that it jumpstarted Janigian’s work.

Barba pointed out that though there is much action, the dialogue is what moves this novel. She queried Janigian on a shift in the later books compared to the earlier ones. In the earlier books the main characters do not have mentors and are left alone to fall back on their own resources when they confront challenges. What changed, she wondered?