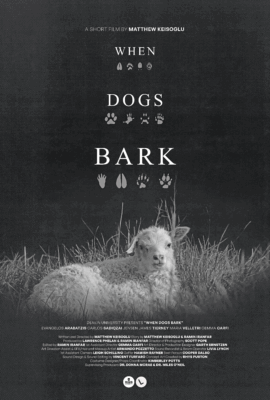

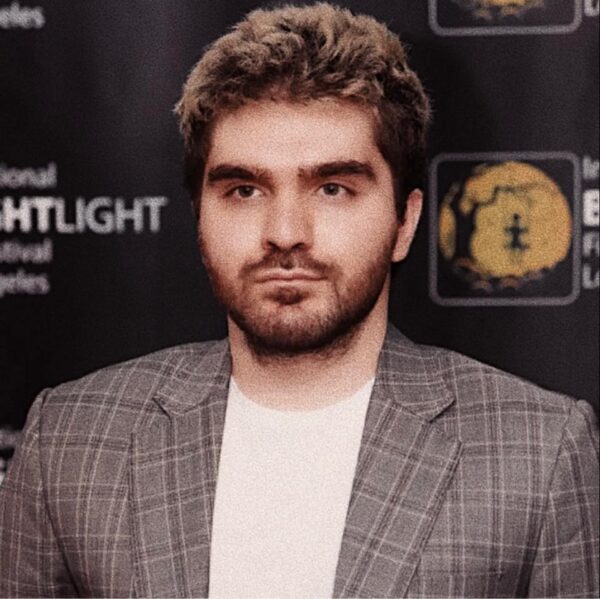

Australian writer and director Matthew Keisoglu recently finished and released “When Dogs Bark,” a short horror film.

In an unspecified place and time, “When Dogs Bark” opens in the aftermath of a slaughter. In a farmland sheep pen, a widowed farmer discovers the mutilated remains of his lambs: corpses torn apart, bones and heads scattered, paw prints in the bloodied dirt. From the wind comes the sound of wild dogs — sniffing, digging, chewing — and with them, the echo of genocide: boots marching, shovels striking earth, children screaming. Memories resurface of a forest years ago, where a young child hid among the bodies as a pack of dogs dragged his mother away.

That child grows into the son, an intellectual who has long since left the shack for the city.

Set in stark black-and-white and framed in 4:3, the film unfolds between the Father’s obsessive listening and the Son’s detached dismissal. Crucifixes, family photographs, mass graves, and pomegranates surround them as sound — owls, wind, soldiers, and dogs — fills the silence.

The film, part of Keisoglu’s master’s degree program at Deakin University, is in Greek and English.

“I come from a family shaped by the Armenian genocide of 1915. Stories passed down to me have influenced how I understand identity, memory, and how history marks individuals and generations. That inherited experience is central to my creative work, but it is not unique to me. Genocide and mass violence have left lasting scars across many regions, from the Holocaust, Cambodia, Armenia, Palestine and Bosnia to Rwanda and Ukraine. The legacies of cultural erasure and systemic violence also endure among Indigenous peoples, including Native Americans and Indigenous Australians. These histories, often underacknowledged, continue to shape identity, memory and lived experience. This film is for any nation that has heard the sound of marching soldiers, the barking of dogs searching for them, and has unearthed the mass graves they left behind,” he said.