Sadness permeates Hovik Afyan’s 2020 debut novel, Red (translated from Eastern Armenian by Nazareth Seferian). The characters in this dark tale inhabit a world of gloom, palpable anguish weighs everything down. If Milan Kundera once wrote about the unbearable lightness of being, here Afyan describes a hermetic universe where an unbearable heaviness of being reigns. The novel is set sometime in the 1990’s, and Armenia is once again at war with its neighbor Azerbaijan. Wood and food are scarce, young men are being sent off to Artsakh to die on the front, and even those who stay behind wage a personal war of their own: with family and friends, and with society-at-large, not to mention with themselves as they face their own inner demons.

Red’s main protagonists, Arus and Aram, are a couple grown weary of each other by the time we meet them in the novel’s opening pages. Unable to have children, they slowly turn away from each other: “Arus and Aram had begun to perceive each other as they were, which was always stressful and inevitable, especially when their desire to have children had been defeated over the years in the battle against their inability to do so.”

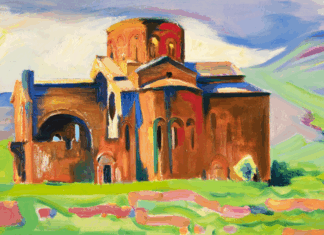

Aram is a talented painter who has survived a difficult childhood ruled by a disciplinarian mother who once gave away all his paintings to a neighbor to be used as kindling to keep her family warm in winter. Much to Arus’s dismay, Aram has recently taken to painting female nudes from live models. This becomes particularly glaring for Arus when he decides to use one of her friends as a model for his behind -closed-door sessions. As for Arus, she is a dancer whose performances Aram chooses not to attend, even though he knows that this wounds her. Aram comes off as being emotionally brutish, but we are made to understand that this is largely the result of his upbringing. Arus eventually gives up dancing altogether of her own accord. One day, as the couple drives to the Artsakh border they encounter something truly gruesome lying on the road ahead, and they will never be the same again.

Meanwhile their friend Frunze and his Lebanese cousin Raffi, a deluded youngster who fancies himself some type of latter-day fedayee, join the war effort in Artsakh, and are soon taken prisoner. A brave villager who returned from a previous war missing a leg, crawls over the border from Armenia and kidnaps a young Azeri girl named Leyla, so they can barter her against the two Armenian hostages. The rather remarkable remaining plot twists and developments leave the reader with a decidedly less favorable view of war than the narrator who acknowledges all its destructive aspects, but also praises the heightened passion and bravery that s(he) feels it elicits in people.

Stylistically, Afyan’s prose possesses a certain Hemingwayesque quality, composed as it is of largely declarative sentences, which include equally pared down prose descriptions and terse dialogue. These are interspersed with debatable — or at the very least subjective — statements and philosophical disquisitions on love, war, ethnic rivalries and the human condition in general.