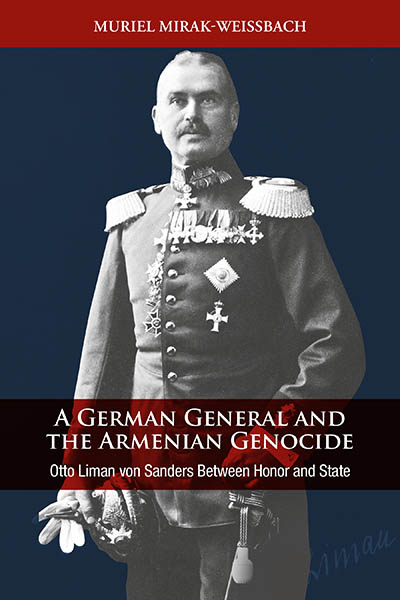

In her latest book, author and reporter Muriel Mirak-Weissbach pays tribute to — or better yet sets the record straight regarding — Otto Liman von Sanders, a German general who served in the Ottoman Empire in the era of World War I and the Armenian Genocide.

A German General and The Armenian Genocide: Otto von Sanders Between Honor and State, in a sober and methodical way, weaves together the various strands comprising the life of the German general who because of a variety of reasons, including honor, did not cultivate superficial relationships with those who could sing his praises to historians and journalists during his lifetime. As a result, he has been tainted by suspicion of collusion during the Armenian Genocide.

Mirak-Weissbach, a regular contributor to this newspaper from her base in Germany, has written several times about Liman von Sanders whose legacy has been unfairly tarnished by history.

The book, published by Berghahn, was released in July. It is a slim volume which offers a helpful chronology and detailed footnotes and sources.

There is a thread of duality throughout the book: German and Ottoman cooperation, Armenian history and German history, a private man versus a public face of a government and a member of an oppressed minority struggling with discrimination while representing a great power. In it, Mirak-Weissbach also weds the two strands of her life, a German resident as well as an Armenian-American descendent of survivors of the Genocide.

Mirak-Weissbach paints Liman von Sanders as an upright though not always likable figure, one who tried to do the right thing, even if it meant experiencing hardship or creating an uncomfortable situation.