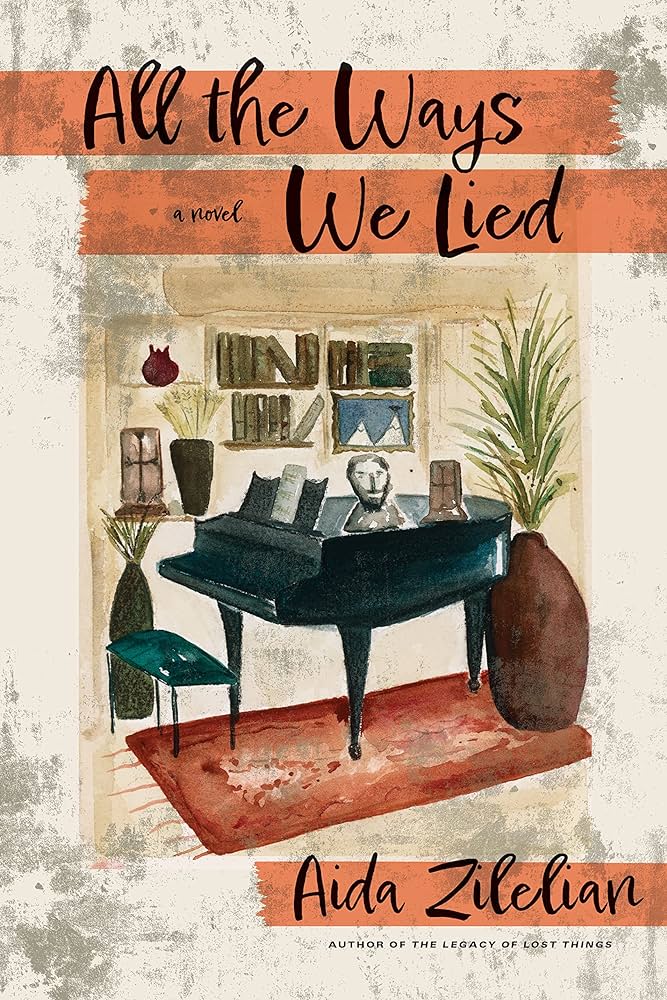

One leaves Aida Zilelian’s All the Ways We Lied (Keylight Books, 2024) with the comfort of knowing that the Manoukian sisters, Kohar, Lucine and Azad, each unhappy in her own way, will always have one another to go to no matter what the challenges life throws their way. Zilelian draws the reader into the intimacy of the sisters’ world with her vivid dramatizations of their endless bickering. Their frustrations and their hatreds come out, but so does the unyielding connection they have to one another. The hugs inevitably follow the hollering.

The novel depicts the life of the Manoukian family, a modern-day Armenian-American family living in Queens. The Armenian culture is clearly there; the characters all have Armenian names and cook and eat traditional Armenian foods. While the parents still believe that Armenians should marry Armenians, however, the daughters, “unlike other Armenian girls,” are fully immersed in their American friends’ way of life, quite at home in their surroundings. They move out, marry odars, go to music festivals in the desert — ansovor for an Armenian girl — and attend the Ayahuasca retreat for therapy. The youngest daughter Azad hangs out with her American friends, “passing around a bottle of liquor and a joint.” The two worlds are so inextricably intertwined it would be difficult to trace their chaotic lives directly to a history of displacement.

All the Ways We Lied is themed around exploring close family relationships. Takouhi, the mother, twice married, is central to much of the action that unfolds. Her disapproval and unfair treatment of her daughters — two are from her earlier marriage — her erratic moods and chronic depression are at the root of the feelings of failure and alienation that plague the sisters’ lives. The vicious arguments the eldest daughter Kohar, always “bold and forthright,” has with her mother reveal the frustrations and the anger of both. Life for Kohar is a “dreadful nightmare.” When she moves out to be away from the mother’s constant accusations — “I’m going to come over one day and reorganize this whole mess for you” — Takouhi stops talking to her. She in fact disowns her daughter completely. In order not to “ruin the family“ and experience the same rejection her older sister had experienced, the middle sister Lucine decides not to move out, and hastily marries her “loser” husband Steve.

Takouhi’s traumatic past might “explain” her “brutal rage” and her mercilessness. Takouhi had been deprived of her childhood dream of becoming a singer when her father had rejected the offer to send her to the Conservatory in Beirut. Her forced marriage to a coarse, often violent, husband might also “explain” some of her irrational behavior. It is difficult to understand however why, after losing Gabriel, the man with the “kind, beautiful face” she had divorced an abusive husband to marry, and with whom she had lived happily for thirty years, a man whose grave she dutifully visited every day after work, Takouhi should suddenly decide to travel, in her outraged daughters’ words, “to the other end of the world,” to the dust and the sand of Togo in West Africa, to marry a twenty-nine-year-old African cab driver she meets online, “to find happiness and freedom.” The blatant irony of her, “I’m doing what I want to do. I’m going. End of story,” and of her earlier sarcastic, “You want what you want and the rest of us have to deal with it” to her daughter Kohar, when the latter had decided to move out, invites a deep probe into her psychology. It is not on moral grounds that one questions Takouhi’s sudden romance. A writer selects her material to fit the “artistic context” of her creation. Takouhi’s behavior might just not be apropos the character Zilelian has created for us. A novel is a construction after all.

On a different note, Zilelian’s non-judgmental stance forces the reader to ask her own questions — What does it take to be happy? What does it mean to be free? — and to seek her own explanations, a probe that should ultimately lead to a better understanding of human connections. Indeed, good fiction, to borrow the words of celebrated writer Annie Dillard, leads to a “more thoughtful interpretation of the world.”

[Spoiler alert:] All the Ways We Lied does not end with, “They lived happily forever after.” Things fall apart. Kohar is alienated from the family, too stressed to produce milk for her newborn daughter. Lucine is silent and gloomy. Her “loser” husband disappears with her savings, “all the money she had collected since filling private orders at the bakery” where she worked. Azad drifts from one relationship to another, while Takouhi remains basically unchanged — even if she has moments of redemption as when she hugs Kohar at the baby shower, “a rare gesture.” Gabriel, the father who, they were all agreed, had kept the family together — even his step daughter Lucine secretly preferred him to her own dad — has died. “The mammoth of a man [Kohar’s husband Jonathan] had loved so dearly had vanished. . . . The house would no longer feel like a home.”