YEREVAN/TALLINN — Estonian writer Kalle Käsper (born in 1952 in Tallinn) graduated from the Russian philology department of the University of Tartu and the Higher Courses for Scriptwriters and Directors in Moscow. He is the author of seven collections of poetry, about 20 books of prose, and a number of plays and screenplays in Estonian and Russian. In 1996, his first novel, Ode to Morning Solitude, won a prize at a novel competition. Between 2002 and 2014 he created the eight-volumes epic, Buridans, which was awarded the Tammsaare Prize, given every five years for a work in the novel genre.

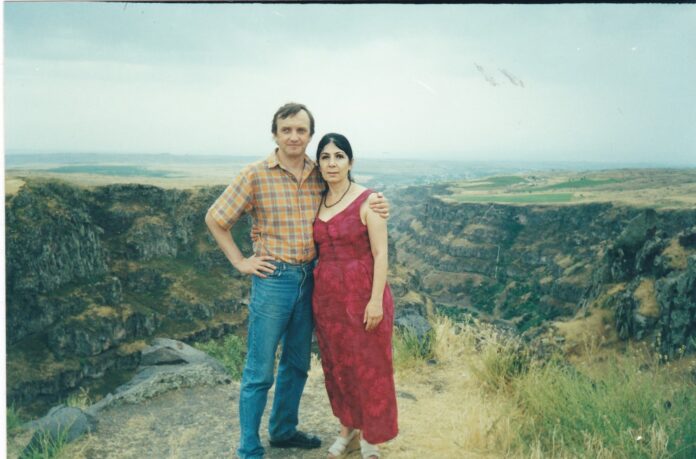

Kalle Käsper is connected to Armenia through his marriage to the Armenian Russian-language writer Gohar Markosian-Käsper (1949-2015), whose works have been translated into all major European languages. His novel Miracle (in Russian) is dedicated to Gohar’s memory and was nominated for the Russian Booker Prize in 2017.

Dear Kalle, fate has brought you together with the Armenian people, and I would like to start our conversation with the talented and unforgettable Gohar Markosyan-Käsper, whose works I have read with pleasure for many years, and thanks to whom I have also become acquainted with your work to some extent. I was not lucky enough to meet Gohar, but it is obvious from her literary style that she was an erudite, ironic, kind-hearted person with a subtle sense of humor.

First of all, dear Artsvi, let me express my sympathy with the tragedy of Artsakh. Sharing your pain, I am nevertheless confident that your people, who have gone through such severe trials, will be able to cope with the current one as well. Strength to all of you for that!

Now about Gohar. You are right, she was not only talented but also extremely erudite. I developed the habit of asking Gohar in search of an answer to some question, before going to the bookshelf with encyclopedias, and usually the reference book was not needed after that. Gohar’s father, opera singer, bass Carlos Markosyan, was a fanatical bibliophile, he collected a magnificent library on which Gohar and her sister Hasmik [ballet scholar Hasmik Markosyan – A. B.] grew up. Gohar loved thick novels — Balzac, Zola, and also fiction, read everything in this genre, and wrote fantastic epic The Fourth Beta. She knew history very well, being especially interested in the Ancient World — this passion, in the end, gave birth to the novel, Mycenae, Rich in Gold, about ancient Greece in the era of the Trojan War, about Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, Cassandra and Orestes.

When we first traveled to Italy, Gohar served as my guide — she already knew what to see first, based on the books she had read. At the end of her life, she started to write a guidebook to Italy, which remained unfinished: I have completed the work, and I hope this book will reach the reader soon. But apart from such general erudition, Gohar, as a doctor, PhD in medical sciences, possessed specific knowledge that was not available to “mere” mortals. She thoroughly knew anatomy, chemistry and biology, and all this knowledge, plus medical experience, helped her in her literary work. She looked at life the way doctors look at life: soberly.