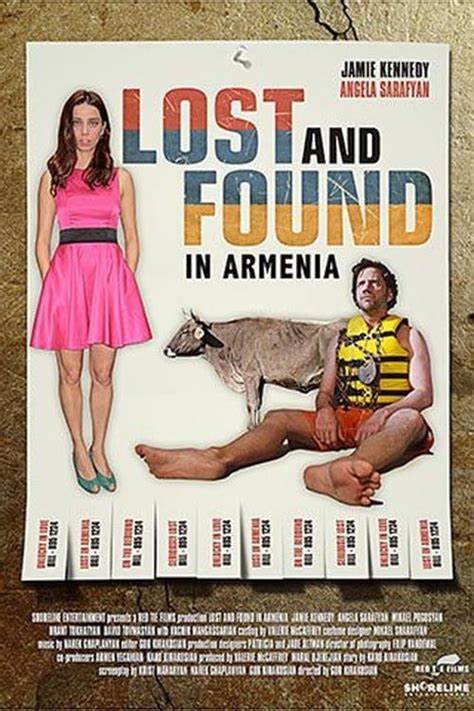

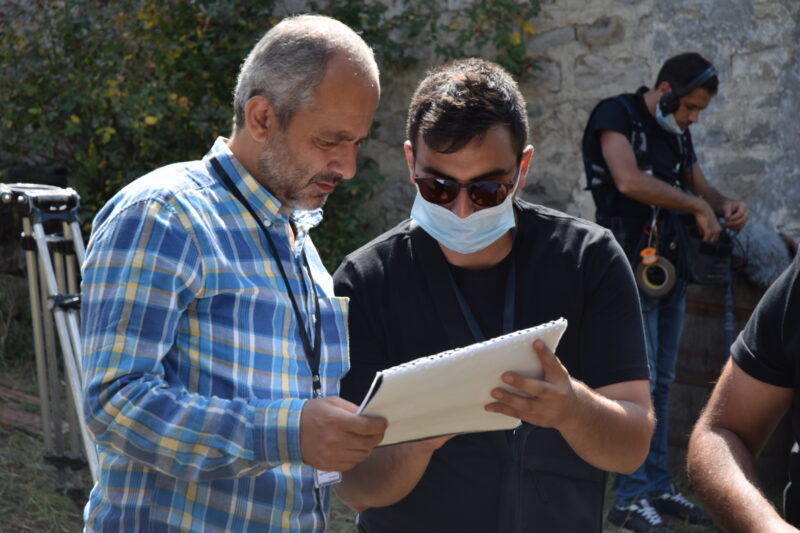

WATERTOWN — Usually when we think about the creators of films the names of directors or producers, or maybe scriptwriters, come to mind, alongside the actors. We seldom think about the art and technical aspects involved in the actual filming. Forty-five-year-old Arman Ordyan, director of photography in feature films like “Zulali” and “Big Story in a Small City,” reveals his experiences over more than two decades in various aspects of filming in the Republic of Armenia.

The Road to Film

As a student, Arman was very interested in drawing and mechanics. He would bring pieces from his mother’s workplace to make car alarm systems at home to earn some money. He joined an afterschool program or club on cosmology organized by the paramilitary Soviet sports organization DOSAAF [Volunteer Society for Cooperation with the Army, Aviation and Navy] and did experiments, participated in discussions and even built model rocketry like space shuttles. Ordyan said, “I thought that there was something there that broadened my world view – that everything is not small but much larger. That, I think, gave me something great, on how I view things even today.”

Arman first was accepted to the Foreign Economic Relations and Management Institute, a private university, and the next year also applied to the Agricultural Institute’s Mechanization, Material and Technical Management engineering specialization, whose buildings were only 200 meters distant from those of the Economics Institute. Arman soon had to leave for his army service, and when he returned, he only needed to pass the final examinations for the Economics Institute, and needed one more year at the Agricultural Institute.

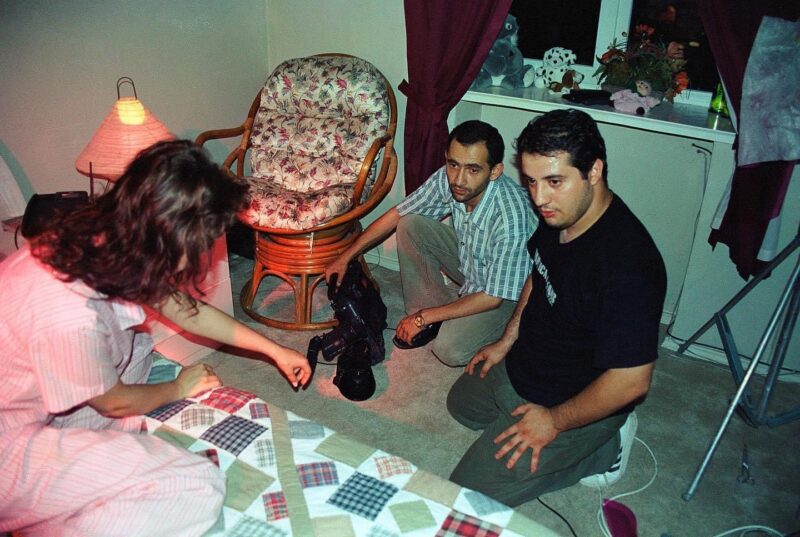

Arman was filming video clips with a small camera when his aunt came to visit from the US in 1999 and traveled around the country. The aunt was a friend of Arsen Aslanyan, who was director of the Kroong Armenian Pop Music Festival and several other programs, so she invited Arslanyan to the Ordyan home. Arslanyan was impressed by the quality of Arman’s work as an untrained amateur, and invited Arman to work with him as a cameraman.

“I asked him what that was because I didn’t know at that time,” Arman said. “After going several times, I realized I liked this field very much.” He also decided he didn’t need to continue his formal education at the two institutes where he had been studying because, he said, everything was corrupt and diplomas were merely formalities at the time.