RACINE, Wisc. — This past year the community of St. Mesrob’s Armenian Church in Racine celebrated its 100th anniversary with special banquets, picnics, and visits from high-ranking clergy.

Founded by immigrants from Anatolia and Western Armenia at the turn of the 20th century, the Armenian community of Wisconsin has always had its largest stronghold in what might seem like an unlikely place: Racine, a small industrial Rust Belt town on the shores of Lake Michigan, set between the large metropolises of Chicago and Milwaukee.

At the same time very Americanized, yet steeped in Armenian traditions brought by the early immigrants, this unique community has marched to the beat of its own drummer for the past 100 years, and has often anticipated developments that would not be seen in other Armenian-American communities for decades. The tight-knit community life, social outreach and community service, and independent spirit of the Racine Armenians is evident to anyone who has visited the community. These traits are tightly wrapped up with their Armenian heritage and faith, as well as a very specific shared background. With very little immigration since the Genocide Era, most local Armenians trace their ancestry to the small town of Tomarza and its five surrounding villages, in what’s now Central Turkey.

Keepers of The Flame

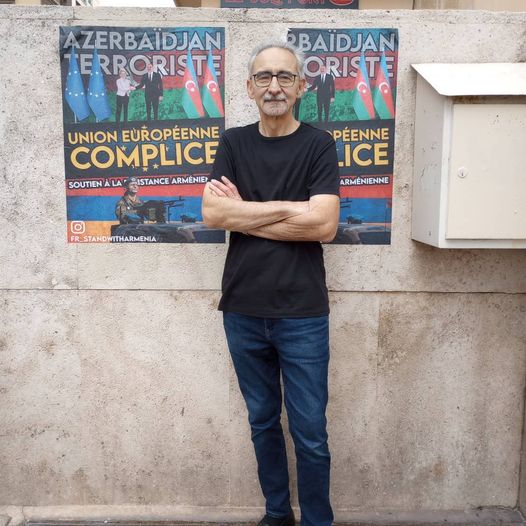

You would not except someone with the name “Chuck Hardy” to be easily the most traditionalist Armenian in an entire US state. But Deacon Charles Hardy has been the staunch pillar of Racine’s Armenian community for some 50 years. Contrary to his name, both of his parents are Armenian; his father’s surname, “Kherdian,” was too difficult for the officials to spell when he tried to apply for citizenship. After being turned away several times being told “we can’t understand what you’re saying,” Hovhannes Kherdian came up with an anglicized name, “John Hardy,” and finally got his citizenship papers. As for Chuck, his baptismal name is Garabed, which was often anglicized to Charles in that era.

Chuck Hardy was born and raised in Racine and is quick to say that not all Racine Armenians are from Tomarza. “The first Armenians to come to Racine were Kharpertsis, and they eventually brought a Tomarzatsi to act as their cook, and he brought in more Tomarzatsis, and they became the majority.”