PASADENA, Calif. — I cannot think of anything more challenging than teaching Armenian language and culture to students in a non-Armenian public school setting. Nonetheless, that is precisely what the twenty-five honorees attending the Armenian Teachers’ Appreciation Night at the St. Gregory the Illuminator Armenian Apostolic Church in Pasadena, on December 11, have committed themselves to doing. These women (all women, alas!) teach in the Glendale Unified School District in a program that makes the teaching of Armenian language to elementary school students part of the school curriculum.

Recognizing that a culture cannot be preserved and passed on to future generations without fluency in its language, Glendale Unified Board of Education President Nayiri Nahabedian, who was present at the event, established the program in the 2009-10 school year, with the full support of the administration. Nahabedian advocated changing the existing Armenian Heritage program, started in 2006-07, to the Armenian Dual Language Immersion program, where students “learn to speak, read, and write in Armenian through content, not as a separate course of study.” All subjects are taught in both English and Armenian.

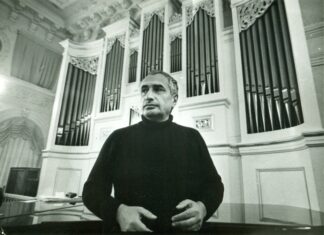

The evening was organized by the Zvartnotz Cultural Committee of the Western Diocese of the Armenian Church of North America on the occasion of the 11th anniversary of its founding. While it aimed to honor all teachers of Armenian language and culture, the event was dedicated to the diasporan poet and educator Vahe-Vahian, in recognition of his legacy, and in hopes of guiding future educators with his example.

After committee chair Dr. Simon Simonian’s welcoming remarks, Dr. Minas Kojayan took the podium to introduce Vahe-Vahian the poet. Learning that the poet’s pen name (his birth name is Sarkis Abdalian) was the name of a temple built by a pagan cleric in our pre-Christian era to store the treasures and the knowledge available at the time was illuminating. The poet’s adopted name reaffirmed for me the true Armenian spirit, that reaches back into our prehistory, of a poet who is revered in both the homeland and the diaspora for, to borrow his words, the “flight of the mind” and “visionary dreams” (a golden bridge).

Dr. Kojayan spoke about the significance of Vahe-Vahian’s various poetry collections. He cited Monument to My Dearest Vahram, 29 poems that describe the poet’s shock and grief at losing his son in a tragic accident, “too early, too soon,” as evidence of his endurance and indomitable will to go on. “There is no lament here,” averred Kojayan. A poet who, at the age of six, had witnessed over a million of his people, “uprooted and weeping along with him,” perish in the Death March during the1915 deportations and massacres, firmly believes that his people will come out of a past of “darkness and ashes” into a future of light.

The sun is ever present in Vahe-Vahian’s poems. To “always soar upwards” and reach for the sunny peaks of the mountains of Arakadz and of Ararat is his guiding belief. Indeed, fighting with a purpose, coming together in peace, and surviving, are the keystones of his creed. “The world needs relief from pain,” he writes in Monument to My Dearest Vahram.