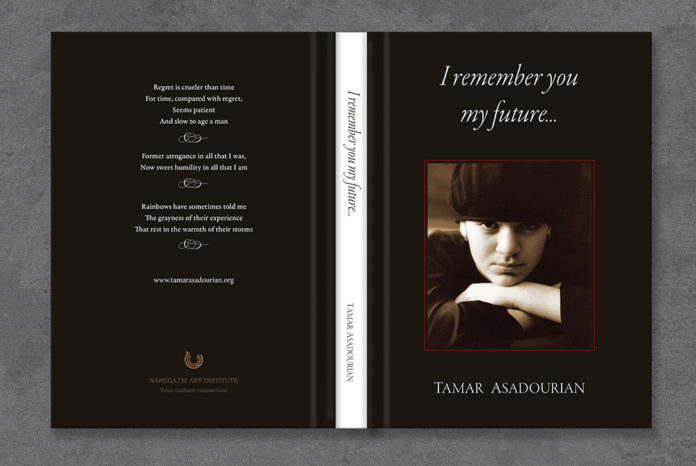

A “new unspoiled unchained order,” where the extraordinarily gifted are free to live in their own “solitude,” and not in an “isolation” imposed on them by the “chains” of the existing order, is what Tamar Asadourian seeks:

Let the mild breath of God disperse the boundaries

of understanding.

Let the very deep azure of solitude reveal its angels

and replace isolation.

Finally let the autumn leaves and cold rocks and fresh mud