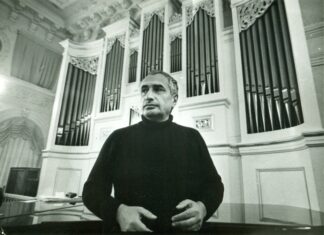

YEREVAN / ATHENS — Film director, producer, and creative writer Vasken Berberian was born in Athens and lived in Italy for more than 35 years. In 1977-1982 he studied engineering science at University of Toronto and has worked most of his life in advertising. He is author of short stories, scripts and novels. In 2011 he co-authored with Sonia Raule Like Sand in the Wind, about an Armenian woman, survivor of Spitak earthquake, who finds refuge in Italy. The novel has been published in English in 2014. His Italian novel Sotto un cielo indifferente (Under Indifferent Skies, 2013) was awarded the recipient of three major literary awards: the Premio Acqui Storia, Italy’s most prestigious literary award for historical novels, Prize Horcynus Orca and Prize Ippolito FNISM. It has been translated into Greek, English and Russian. As the book announcement states: “Under Indifferent Skies is an enticing novel, recounting the story of the Armenian genocide and beyond, from the shores of the Mediterranean to the frozen Siberian coast, from the plush palazzi of Venice to the cruel Soviet concentration camps, following the lives of two twin two brothers, Mikael and Gabriel, and their younger sister, Rose. The story moves in space and time against the background of many of the significant historical events of the last century which shook the very foundations of humanity. It is compelling, full of suspense and unexpected narrative twists.”

“Vasken Berberian is undoubtedly one of the most powerful and authentic literary voices of present-day Italy. He shows he is an interpreter of the deeper meaning of History. Through his literary filter he manages to reweave the painful fate of a family in a style which revives the canons of ancient Greek tragedy. For this reason, our jury has decided to award him the prize for the Best Historical Novel of 2014, in acknowledgement of the ethical/epic value of his book and his ability to portray articulate, complex and evocative scenarios” (from Acqui Storia Prize’s jury’s official press release).

Vasken, first I learned about you as the director of 1997 short Italian film, “Amen.” As far as I understand, you have made advertising films, but what film is “Amen?”

“Amen” is a tribute to postmodernism, inspired by Bret Easton Ellis’ books, which fascinated me at the time. The film is about a rock star and his huge ego who, gradually, comes to terms with his shortcomings.

Being Greek-born Armenian your literary language supposed to be Greek, but you are an Italian writer. How so?

I’ve literally grown in Italy, at least mentally. Writing in Italian came as a natural consequence. If one’s mother tongue is important, it’s even more so the language one has matured with.