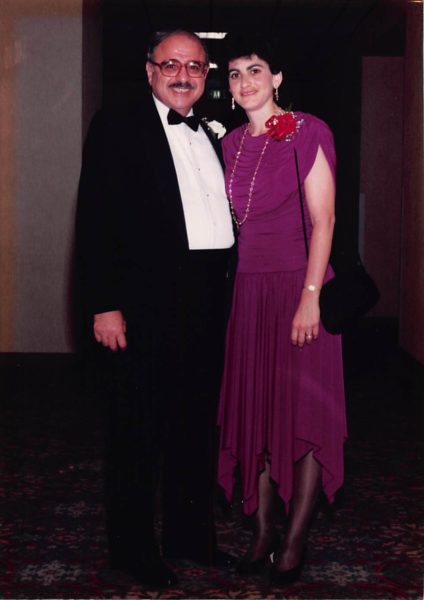

SAN JOSE, Calif. — It is hard to come up with a comparable living Armenian-American couple, as prolific and influential in the community, and as nationally respected in their fields, as Drs. Dennis and Mary Papazian.

The recent publication of Dennis Papazian’s memoir, From My Life and Thought: Reflections on an Armenian-American Journey (Fresno State, 2022), offered an occasion to interview the duo from their Bay Area home.

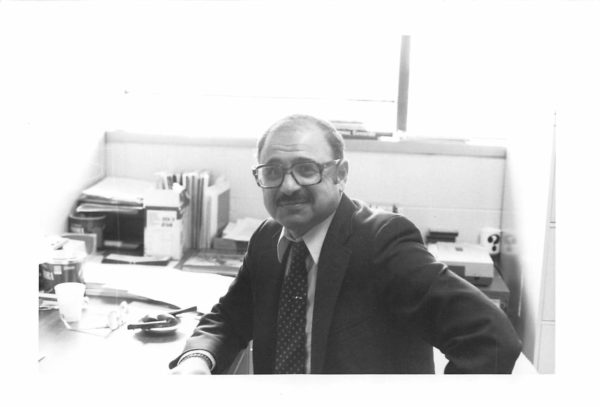

Dennis, 90, is a former administrator, professor of history, and director of the Armenian Research Center (which he founded) at the University of Michigan – Dearborn, was also instrumental in Armenian-American political life, as one of the founders of the Armenian Assembly of America.

Mary, who started her career as a professor of English at Oakland University in Rochester Mich., quickly moved into administration as well, serving at Oakland, Montclair State (New Jersey), Southern Connecticut State, and San Jose State.

Their accumulated experience and combined CVs seem only to be made exponentially greater by their marriage, through which they have supported each other not only personally but professionally and in their service to the Armenian community.

Cold War Professor