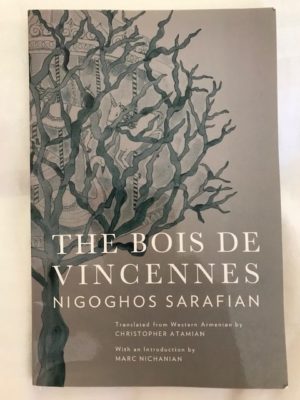

Nigoghos Sarafian’s The Bois de Vincennes (Wayne State University Press, 2011), hailed as one of the most important texts of twentieth-century Armenian diasporic literature, transports the reader to a land that exists somewhere between the intangible reality of legends and dreams and the material reality of a forested world with lakes and waterfalls, extending from the Marne, on the outskirts of Paris, to the Don and beyond. In this enchanted land trees come to life and communicate with one another. Branches break and scream in agony. At times, the trees turn into witches, demons and gypsies, but they can also be angels who “whisper of a lost heaven.” This magical world is brought to us through the musings of a narrator, an exile, “homeless and alone” in an alien land, searching for the beauty and the truth that perhaps only one’s homeland can give. “I can’t stop my tears from flowing when I hear a song from my native land,” he moans.

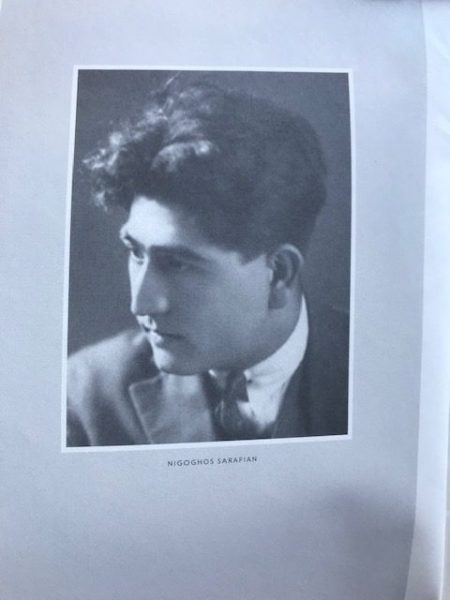

Sarafian himself spent his entire adult life in Paris. He was born in Bulgaria and lived in the Ottoman Empire until he was exiled from his native land following the 1915 Armenian Genocide. Much like the narrator, Sarafian was stubbornly trying “to give meaning to an absurd life,” always consumed by the fact that he has “nowhere to put down my roots . . . nowhere to lay anchor, no safe haven.”

The book ends on a note of renewal and rebirth. The narrator is “alive, vigorous, and victorious.” Beauty is, once again, the source of joy. The woods are “enticing,” “bewitching,” “magical,” “infinite.” Nevertheless, it is the “silent suffering” of the narrator, his fears, his doubts, and the horrors he still “carries within him,” that one leaves the book with. “Oppressive reality remains within me at all times,” he confides.

In the darkness of the solitary woods, away from the city’s rumbling and from cars constantly rushing by with their lights, the narrator meditates on the death and the destruction mankind has inflicted upon itself. He conjures his memories of the bombings of the wars he lived through. The 1915 deportations and the massacres are evoked through his visions of dead bodies and deportation guards. Once in a while a tear falls from one of the trees and drops on his head, “And sometimes when a storm explodes out of nowhere, the trees are an entire people massacred and sent into exile.”

The Bois de Vincennes does not reflect despair, however. The narrator’s, “We can’t escape the human condition, so why do we insist on trying?” is not an expression of weariness. Sarafian’s is an attempt to confront the human condition in all of its misery and senselessness. Accepting life’s pain frees man from the illusions of “hope,” and brings him closer to the truth about the mysteries of life, a truth so poignantly expressed by celebrated nineteenth century American poet Emily Dickinson: “I like a look of Agony,/Because I know it’s true.” In fact, the narrator lives with ”always that dreaded fear of fooling myself.” Hope is something only the weak cling to. “It’s easy to believe and to hope. What is truly difficult is to carry despair and doubt within oneself,” writes Sarafian. Daring makes us stronger and, as the narrator well knows, it “makes life more beautiful, taking it beyond deceit, at the price of solitude, suffering, and being rejected by others.” Even if the self has little more than obsessions and dreams to go through life, facing up to its truth keeps human beings human.

The feeling of alienation is not unique to Armenians. “Who am I?” is perhaps the quintessential question of twentieth century thought which is dominated by a tragic sense of loss following the disappearance of the certainties and the standard beliefs of past centuries. Yet, having the question posed by Sarafian with such originality came to me as a revelation. The Bois de Vincennes links the absurdity of the human condition — “Who am I? “ “Where is my true self?”— to the emotions that spring “from the depths of our suffering.” The narrator’s, “my injured people,” “my tortured people,” “my lost homeland,” give his pain an immediacy that adds immensely to the book’s appeal.