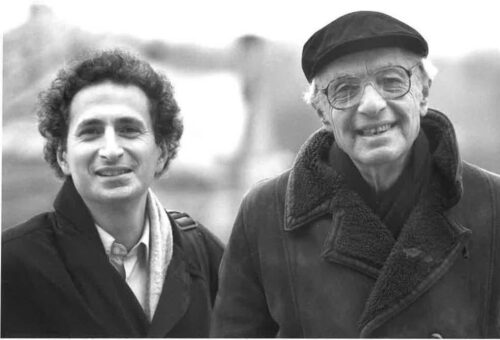

WATERTOWN — Wherever Armenians have established communities in corners of the world distant from their homeland, they have built churches. After that, in many places come schools. Museums are another way of preserving and presenting Armenian culture to the world and to new generations of Armenians too. The Armenian Museum of Moscow and Culture of Nations has begun to play this role in Russia. Museum founder Ruben Tsolakovich Grigoryan related the complicated circumstances of its development.

Grigoryan was born and educated in Yerevan, while his father’s family originally came from a village in Moush (Western Armenia). After graduating from the Polytechnic Institute in Yerevan as a radio engineer, Grigoryan moved to Moscow in 1986 and worked in an educational institution, teaching specialties such as engineering and electronics.

After a period in Germany, he returned but the Soviet Union collapsed, so Grigoryan went into the real estate business, primarily in investment, construction and management, and soon became quite successful. He also graduated from the State University of Management in Moscow in 2002 with a doctoral dissertation on small business management and authored several books starting in 2017. He has carried out various philanthropic projects in Armenia and Karabakh.

The Construction of the Cathedral Complex and Museum

In the Soviet period, only one Armenian church was permitted to operate in Moscow. After the Soviet collapse, as the Moscow Armenian community continued to grow, it decided to build a cathedral and a surrounding complex of buildings, in which eventually a museum was to be established. Grigoryan said that thanks to the initiative of several prominent Armenian businessmen, the Russian authorities had provided a wonderful plot of land in the center of Moscow for this purpose in 1998. It is located in the Meshchanskiy District.

There are probably over one million Armenians now in the Moscow area, Grigoryan estimated, but they live all over and there are no special Armenian neighborhoods. For this reason, the location of the church complex in a central location is important because it can be easily accessed via metro and other public transport, as well as driving.