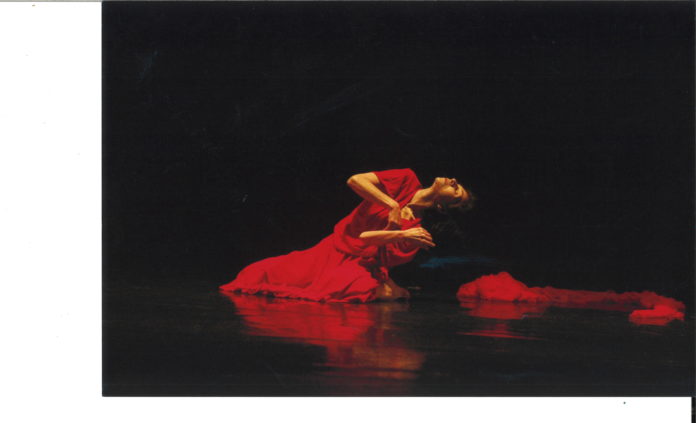

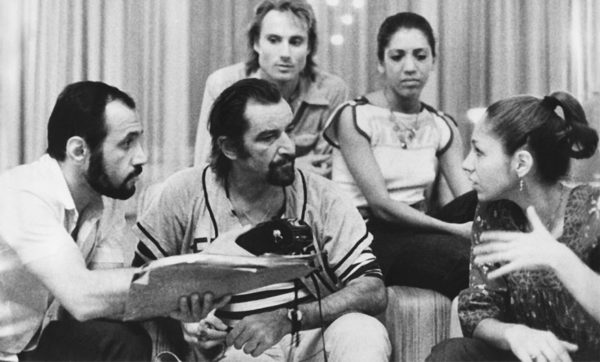

YEREVAN / GLENDALE — Aida Amirkhanian is a choreographer and performer in dance theatre, as well as a yoga teacher. Born in Tehran, she graduated from the world-renowned École Mudra in Brussels, Belgium under the direction of legendary choreographer Maurice Béjart, where she studied dance, theatre, music, improvisation and interdisciplinary composition. She has performed internationally with École Mudra and Béjart’s Ballet du XXème Siècle for several years including performances at the Covent Garden in London, Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus in Athens and the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires among others.

In 1982, Aida moved to Australia where she continued her multidisciplinary career as a choreographer, performer and theatre director working in collaboration with many dance and theatre companies including the Human Veins Dance Theatre, the Canberra Dance Theatre, the Jigsaw Theatre Company and Women on a Shoestring Theatre Company in a variety of capacities.

Aida has been based and continues her artistic journey in Los Angeles and has been creating and performing new solo works as well as collaborating with various artists. She has also performed in Dance Kaleidoscope festival, Fountain Theatre’s Festival of Solos and Duets and Interplay Santa Barbara among others. In 1991 Aida was the recipient of the Canberra Critics’ Circle Award for her creativity and artistic integrity as evidenced in her choreography and performance over a number of years and as exemplified in “Mephisto Waltz.” In 1992, she completed her solo piece for which she became one of the five finalists for the Canberra Times Artist of the Year award. In 2004 Aida was nominated for the Horton Dance Awards in Los Angeles as outstanding solo performer.

“To say that Aida Amirkhanian is a dancer is a little like saying the Eiffel Tower is a lookout. Certainly, you can take a lift to the top and the view is engaging. But by then you aren’t seeing the tower itself with its lean strength, it’s soaring spirit, its spare design, its truthful lines. You are looking in the wrong place to find its essence – for that resides inside the structure and it is seen only with an inner eye. She is not just a dancer. She is an artist, and dance is part of her art form,” Robert Macklin, wrote in the Canberra Times in 1992.

Aida, first we met in 1998 in Yerevan. Are there some essential changes in your artistic and personal character?

I was very fortunate to have met you more than two decades ago in Yerevan and know you an incredibly knowledgeable, inspiring character that advocated various performing art forms, and for that meeting I am grateful. As about what has been changed — for one thing I am 20 years older and hopefully — a little wiser. I am calmer and yet the life force is still flowing through my veins with intensity, so I have learned a little about subtleties and nuances and maintaining my integrity and using my inner energies mindfully and generously, that is a good thing.