Special to the Mirror-Spectator

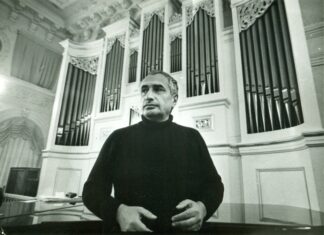

“Today he’s forgotten, the most forgotten famous writer of the 20th century.”

Mark Arax

The reception of a literary text would probably be different if we did not espouse various theories to read literature. In other words, if we approached the text as “common readers,” to invoke the title of Virginia Woolf’s collection of Essays, The Common Reader, we might bring appreciation back into our reading and reclaim “the pleasure of the text.” “The common reader,” writes Woolf, “differs from the critic and the scholar. . . . He reads for his own pleasure rather than to impart knowledge or correct the opinions of others.” This is the reader that Dr. Johnson, the revered 18th-century critic and writer, from whom Woolf borrows the notion of the common reader, “rejoice[s] to concur with.”

It is no secret that for an academic readership literary theory, that is the adoption of various critical perspectives to analyze literary texts, influences the reception of an author’s work. Theory can be very useful. Each new perspective, such as feminist or psychoanalytical, helps us get new insights into the meaning of a text. Yet, adopting a specific perspective as an analytical tool could also “force” a certain “meaning” onto the text to support the theory. More importantly, the emphasis on theory excludes readers who are, in Dr. Johnson’s words, “uncorrupted by literary prejudices and the dogmatism of learning.” These are the readers through whose common sense “must be finally decided all claim to poetical honors,” notes Dr. Johnson.

Academia plays an important role in mediating the popular reception of a text as well. In the United States, the dominance from the 1930s to the 1960s of New Criticism, a critical perspective that separates the work from its author and the context in which the work was produced, may have had something to do with Saroyan’s oeuvre falling out of favor. Much of Saroyan’s writing is “simple” and does not require the close textual analysis that texts with more complicated structures and imagery do to interpret. Thus, an author who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his play “The Time of Your Life” and whose The Human Comedy was required reading in high schools, is no longer on the reading lists of many academic departments.