YEREVAN / ALUKSNE, Latvia — Art critic Inguna Kurcens was born in 1951 in Riga. Her entire family was oppressed during the time of Stalin.

Inguna graduated from the Music College in Abakan (Khakassia, Krasnoyarsk Krai), then the Academy of Arts (1975-1981) in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). She graduated from her postgraduate studies at the Moscow Research Institute of Art History, where in 1993 she defended her PhD thesis on the work of Minas Avetisyan.

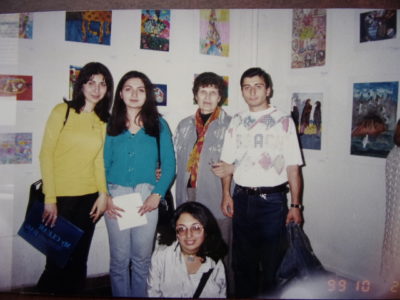

From 1981 to 2000 Inguna lived in Yerevan, worked at the National Art Gallery and Yervand Kochar Museum, taught art history at the Yerevan Art Institute and at the art history faculty of Yerevan State University. Her articles on the Armenian fine arts of the 20th century were published in the Russian and Armenian press of Yerevan, as well as in the Haigazian Armenological Review of Beirut. Inguna Kurcens represented Armenia at international conferences in St. Petersburg and Warsaw. She is the author of the catalogue of artist Eduard Isabekyan’s Moscow exhibition (Moscow, 1988) and a booklet on Minas Avetisyan (Yerevan, 1989, both in Russian).

Since 2000 Inguna has been living in the city of Aluksne (Latvia), where she teaches at the School of Arts and the School of Music.

In 2014, the monograph by Inguna Kurtsens “Minas Avetisyan. Painting and Drawing. (On the Question of the Forms of Associative and Symbolic Imagery in Armenian Painting of the 1960s – 1970s)” was published in Yerevan (in Russian).

Inguna, is it true that your love of Minas Avetisyan’s art brought you to Armenia? How did it come about?