NEW YORK — In 2017, writer and journalist Taleen Babayan turned her efforts to directing a short documentary in Martakert, a village in Artsakh which now stands divided between Armenia and Azerbaijan after the 44-Day War. Her subject is an unlikely trio of young men in their late twenties — Spartak Osipyan, Eric Poghosyan and Lyoka (Valeri) Ghazaryan — who form the Armenian rap group Orinak (“Example”). Unlikely as well, that a first documentary on this particular subject matter should be quite so successful but “Rapping Under Fire” fascinates from start to finish. The boys from Orinak have, after all, survived their entire lives amidst the ruins of the long-simmering conflict, in a region of the world that few people care about. At one point in the documentary, Spartak points to a rusty Ferris wheel where two generations of Martakertsis have now played on a daily basis, a metaphor for the condition of Artsakh: abandoned yet unwilling to give up.

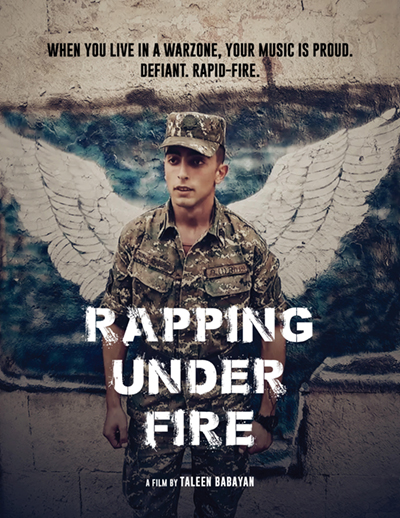

The three discover rap music and adopt its style — “Proud. Defiant, Rapid-Fire,” as the film poster announces — three voices that express the fears and desires of a generation eager for change. They have even started a program to also teach local kids to rap — and how happy they look these primary school children as they strike poses and rap out loud.

What makes for a successful documentary? As with any film, strong filmmaking technique along with a seamless storyline are a good start — and “Rapping” has both. But the film also succeeds in drawing in the viewer and making him or her identify with its protagonists: in the process, the story goes from the particular to the universal.

A beautiful opening aerial pan of Martakert shows off the region’s verdant, natural beauty. Next the film cuts to Spartak, a handsome fellow who is engaged in hand-fashioning wooden coffins, of all things. At one point he looks up and explains that he and his fellow Martakertsis have known only war since their birth: “It’s always been this way, we’re used to it.” And then, in a statement that is both black humor and highly serious, he adds, “One thing never changes…There is always a need for a coffin here.”

One marvels at how these three previously unversed musicians from Artsakh managed to adopt and adapt a musical style created by young inner-city African-Americans to the Armenian language and local dialect.

Of course, today rap music exists in many languages including French, Spanish and Russian, but Armenian culture has remained somewhat isolated and traditional, so Orinak’s music in a way represents something even more remarkable.