In an interconnected world of politics, no crisis can be considered solely local. Reverberations cross the boundaries of any country in question. We may consider Armenia’s current domestic crisis as a local squabble at our own peril, because reactions arriving from many world capitals make abundantly clear that many distant parties have a stake in the situation brewing in Armenia.

Many of Armenia’s current problems are now sidelined by political bickering by many factions which are trying to draw the attention of their constituents to their own agenda.

The challenge to Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan was initiated by a coalition of more than 16 parties which have rallied around Vazgen Manukyan, a former prime minister, demanding Pashinyan’s resignation as the sole responsible person for the defeat in the 44-day Karabakh war.

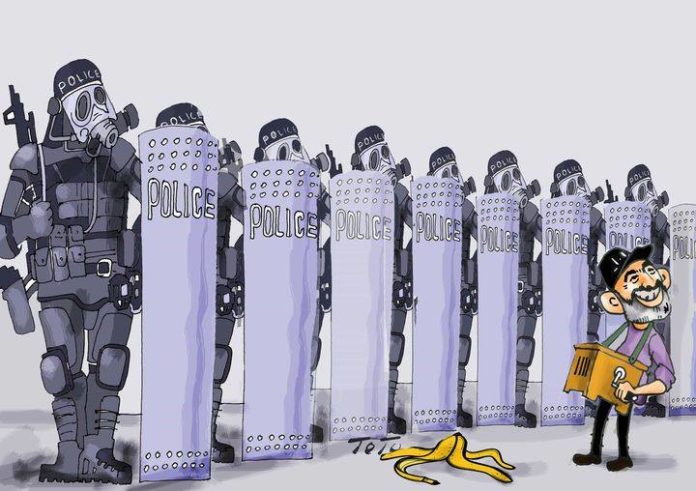

Pashinyan is retaliating against those demands by rallying his own partisans in Republic Square, to demonstrate that he still enjoys popularity among Armenia’s voters. Indeed, he and his My Step alliance were elected with a landslide of more than 70 percent of votes in 2018.

Most recent polls show that while his popularity has plunged, he still has an edge over other contenders with 45 percent popularity.

The problem with Vazgen Manukyan’s camp is that ghosts from the old regime dominate his ranks, in particular, the former presidents and Ishkhan Saghatelyan and Gegham Manukyan from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, a party which has never crossed the threshold of two percent in any parliamentary election.