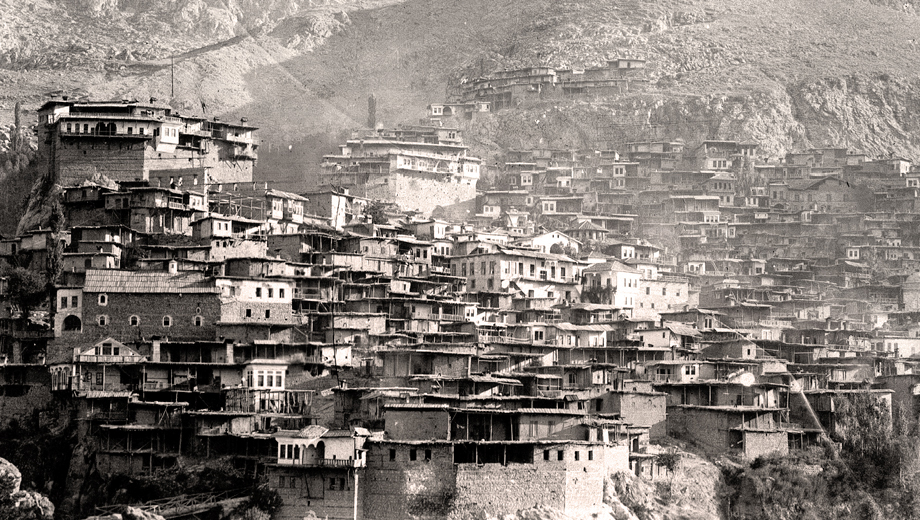

DETROIT — The region of Cilicia occupies a unique place in the history of the Armenians, which began after the incursions of the Turks in Asia Minor in the 11th century and the exile of the Armenian nobility. From the time that Baron Roupen I gained a foothold in the mountains near Hadjin in 1080, the area was to become a second homeland for the Armenian people up until the Armenian Genocide of 1915.

Thousands of Armenians and even the Catholicos had followed the exiled nobles to the area, and even after the Kingdom fell in 1375 and the Catholicosate returned to Echmiadzin in 1441, Cilicia remained home to a vibrant Armenian community. Its chief bishop retained his status of Catholicos as well, though subordinate to Echmiadzin. In literature, poetry, and song, the Armenian people extolled Cilicia second only to the homeland of Armenia itself. It is no wonder that during the war, so many Armenian young men signed up to fight the Turks as “gamavors” under French leadership in the specially created Armenian Legion, as the Allies promised them a homeland in Cilicia through the intercession of Boghos Nubar, head of the AGBU. Though the Allied and Armenian troops arrived in 1918 and ADL leader Mihran Damadian attempted to declare Cilicia’s independence on August 5, 1920, the French ceded Cilicia to the Kemalist Turks in late 1921 and evacuated their troops on January 4, 1922, forcing the Armenians into a second exile.

One of the earliest songs referencing the Armenians in Cilicia is the Lamentation of Levon. I will here paraphrase the remarks of Puzant Yeghiayan on this song, in his book, History of the Armenians of Adana.

“It is known from the history of the Armenians of Cilicia, that the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt, Baybars al-Bunduqdarr, receiving aid from the Crusaders’ Emperor Frederick II [actually, Frederick’s son King Manfred of Sicily] against the attacks of the unified Armeno-Tatar front, conquered Syria and Cilicia in a counter-attack, and in one fateful blow, Toros, son of King Hetoum I of Cilicia, fell in battle, while his other son Levon was taken to Egypt as a slave in 1266.

It was only four years later that Levon, being freed, would come and sit on the Cilician Throne as Levon III [King Leo II of Armenian Cilicia, ruled 1270-1289].

This little ballad, which repeats the well-known episode from the epic Sassountsi Tavit of Msra Melik playing with the ball, is perhaps a remnant of a Cilician epic similar to Sassountsi Tavit, or, even a prototype of Sassountsi Tavit.”