By Artsvi Bakhchinyan

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

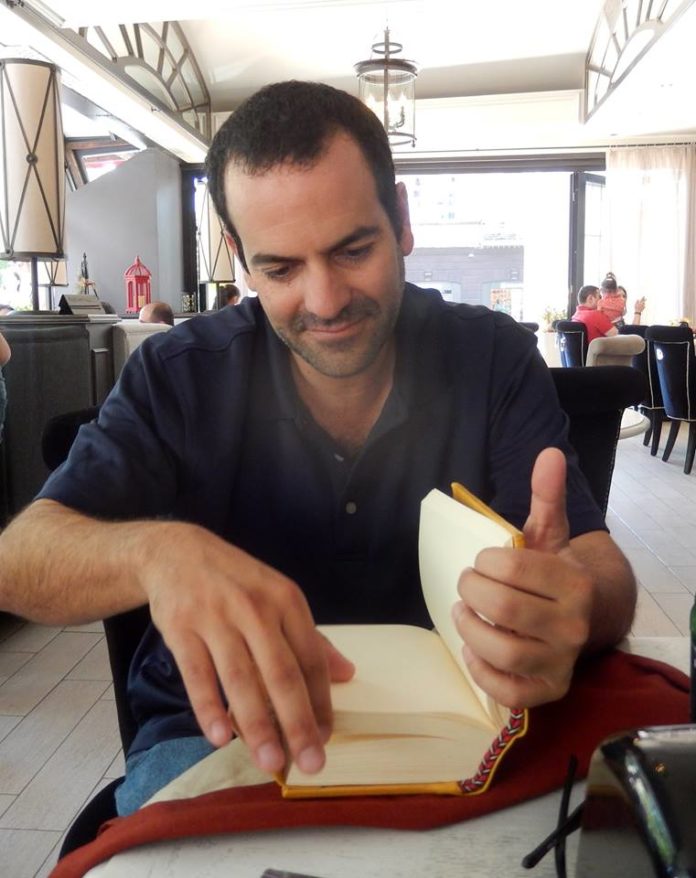

MEXICO CITY, Mexico — Carlos Antaramián is the only Mexican Armenian I have met, one of the active members of a small Armenian community in Mexico, who has been researching the history of this community and other Armenians-related topics. He travels often to Armenia, participating in different events. In 2015 he took part in the events dedicated to the centennial of the Armenian Genocide, and served as an observer in the elections of Artsakh. At the Spanish Club in Yerevan, he screened the film “Armenians in Mexico” by American-Armenian Philip Boyajian, shot in 1957, the only copy of which is in his possession.

Below, Antaramian in his own words tells us about himself and the Armenian community in Mexico:

I was born in 1972 in Mexico. My father, Eduardo Antaramián, was also born in Mexico, and my mother is Mexican of Spanish-Indian descent. My paternal grandmother, Victoria, was from Constantinople, and my great-grandfather, Garabed, from Kharberd area or Charsanjak, Hoshe village, near Peri, today called Akpazar, close to Dersim. I have visited there once. My grandfather Garabed was one of the Genocide survivors. The only thing he said was that his mother and younger siblings had committed suicide by jumping into the river, not surviving the slaughter of other family members. My grandfather was rescued by a Kurdish family; then he went in Aleppo, from where he left for Mexico in 1923. In 2015 I went down to the river to pay tribute to my ancestors who found their end there. By the way, my 6-year-old daughter, knowing where to go, gave me one of her toys and asked me to throw it into the river…

I studied international relations at the National University of Mexico, then social anthropology in Zamora Michoacán. My PhD thesis was about commemoration of the Armenian Genocide in different places. To this end, I have studied commemoration ceremonies in Paris, Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Istanbul, Yerevan, and interviewed various individuals. In my work I try to illustrate and analyze the similarities and differences between the first commemoration of April 24 (in 1919 in Constantinople) to date. For instance, by 1965, for example, our victims were constantly remembered, but no demands were made.