WATERTOWN — The Armenian Museum of America unveiled a new exhibit on April 24 called “In the Shadow of Branches.”

The exhibit, in the Adele and Haig Der Manuelian galleries, presents the work of two women, a diplomat and an artist. The diplomat, Diana Agabeg Apcar (1859-1937) helped save the life of the artist, Berjouhi Kailian (1914-2014), when the latter was a child refugee from the Armenian Genocide. The aftereffects of genocide continued to reverberate in Kailian’s life and art for decades. The motto for the Armenian Museum exhibit is that “individuals who take a stand can impact history exponentially.”

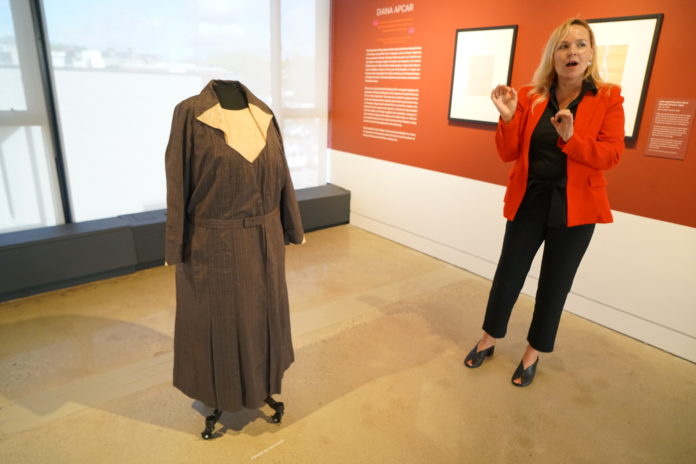

Jennifer Liston Munson, executive director of the museum, provided a press briefing during the morning, while the exhibit opened that evening to the public. Michele Kolligian, president of the museum’s board, welcomed guests at the formal event and Munson spoke about the preparatory work for the exhibit. Questions were then taken from the audience.

Visitors to the newly refurbished and bright third floor galleries of the museum first encounter a display on Apcar, including juxtaposed timelines of events in her life, Kailian’s life, and major international turning points. A projection on a pedestal of the trailer of “The Stateless Diplomat: Diana Apcar’s Heroic Life,” a film being prepared by Apcar’s great-granddaughter Mimi Malayan, makes scenes from Apcar’s life come alive (see it at https://dianaapcar.org/).

Apcar, born in Rangoon, Burma, grew up in Calcutta, India and moved to Yokohama, Japan in 1891 with her husband, who died unexpectedly in 1906, leaving her to run the family trading and shipping business. The museum exhibit showcases a number of her personal effects on loan from the Armenian Cultural Foundation (ACF) in Arlington, Mass., including her watch, fountain pen, cup, card box, letter box, makeup box, and bud vases, as well as a kimono and dress. Her modest Edwardian-style dress and a kimono strikingly point to two of the cultures Apcar managed to bridge.

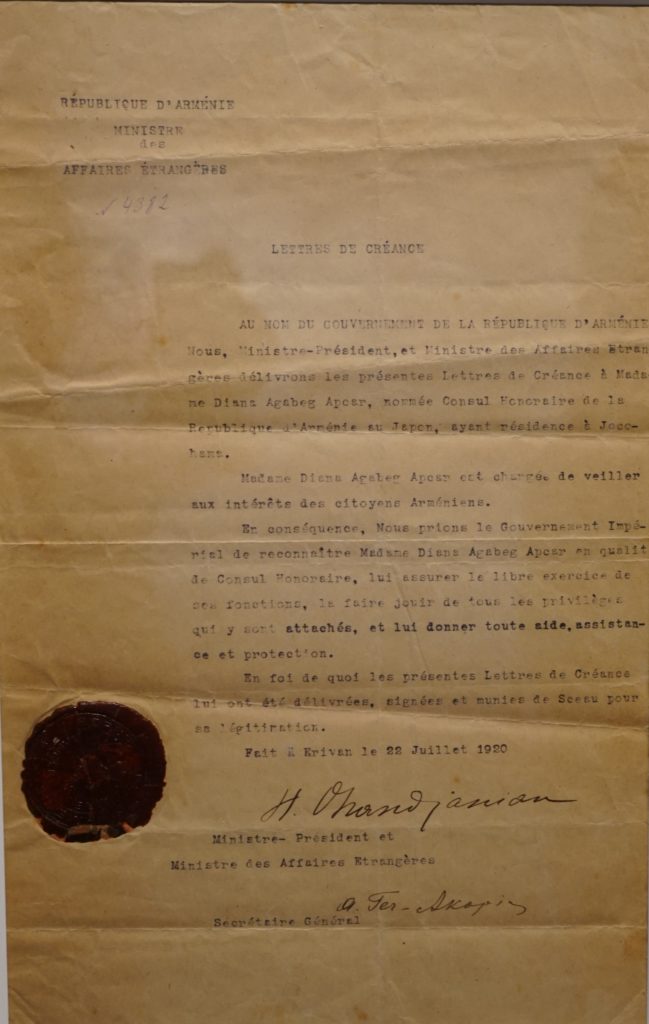

Several of her official documents on loan from ACF are framed. They include the July 22, 1920 letter from Foreign Minister Hamazasp Ohanjanian appointing Apcar honorary consul, her diplomatic credentials, diplomatic passport, her draft letter to a Japanese governor, and a copy of her baptismal certificate. There are also some photographs of Apcar and her family loaned by Project Save Armenian Photograph Archives for this exhibit.