By Archi Galentz

BERLIN — The website of Aravot reported on February 21 on the visit of Anna Hakobyan, the wife of Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, to Switzerland and the surprise that she brought with her. The surprise was her declaration that Armenia would once again amaze the whole world, this time with post-revolutionary achievements. Armenia is to become one of the most prosperous nations in the world, absolutely comparable to Switzerland

Hakobyan supported Pashinyan during the revolution not only visibly and with extensive media coverage, but she is also now leading several charity organizations and is assuming serious representational duties.

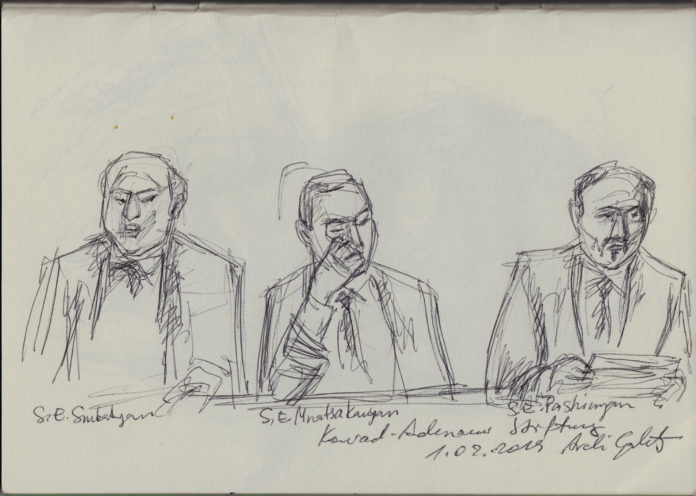

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan himself, during a meeting at the beginning of February with parliamentarians and the business community in the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Berlin, emphasized the fact that Armenia is not only a country with mining and agriculture, but a land of intellectuals, physicists, a flourishing IT sector and, as a member of the Eurasian Economic Union, a country that may also pave the way to access to a market of 160 million people.

And when asked about the planned elimination of the Culture and Diaspora Ministries, which has generated concern, Pashinyan responded that every government mechanism has a tendency towards excessive control and this could have a negative impact on business.

Proponents of streamlining the government apparatus stress that reforms do not entail neglect of spheres of responsibility. Armenia’s desire to introduce new standards of efficiency and its search for new models is also apparent in the cultural realm. In mid-May at the Venice Biennale 2019 we will be in a position to judge whether or not Armenia’s pavilion, which according to the exhibition’s curator Susanna Gjulamiryan this time is not to be organized on the premises of the Mekhitarists, will be convincing. Exhibition space at the Biennale is extremely expensive, but it is reportedly the explicit desire of the government-aligned commissar of the exhibit to invest considerably more than the usual $5,000 in the “Olympic Games of Art.” The Venice Biennale is the most important exhibition worldwide for contemporary art and architecture. It is particularly important to note that at this periodic event one cannot hide behind tradition and history, because its compulsory thematic focus concentrates on the “Now” – the current condition of the nation’s art and its cultural policy. Armenia has been an active participant since 1995 and in 2015 received the highest award, the “Golden Lion,” for its national pavilion. The 2017 presentation displayed very disturbing tendencies, and now what is being prepared is a huge installation of multiple interrelated components with a lot of videos which are supposed to provide a critical view of the “Velvet Revolution,” how it unfolded and what expectations it raised.