CAMBRIDGE, Mass. – A new exhibition called Passports: Lives in Transit is on display at Harvard University’s Houghton Library from April 30 to August 18. It provides an unusual way of thinking about the urgent issue of massive global migration in a historical perspective. It uses passports, visa applications and other documents associated with travelers, emigres and refugees to symbolize what the organizers fear is “the ruins of a modern dream now in terminal crisis — the dream of a globalized word.” The exhibition includes a section showcasing the Armenian Genocide as an exemplar of 20th century exile and escape.

The exhibition materials are drawn from the collections of Houghton Library, Widener Library, Harvard University Archive, Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library, Harvard Business School’s Baker Library, and Harvard-Yenching Library, and are connected with the United States, either as a final refuge or destination, or as a place to flee. Its highlights include the passport from 1857 of George Francis Train, who claimed to be the inspiration for Jules Vernes’ character Phileas Fogg in Eighty Days around the World, Leon Trotsky’s exile papers, physicist Gertrude Neumark Rothschild’s passports, African-American activist (and wife of W. E. B. Du Bois) Shirley Graham Du Bois’s passports and letters, and Timothy Leary’s fake passport photos.

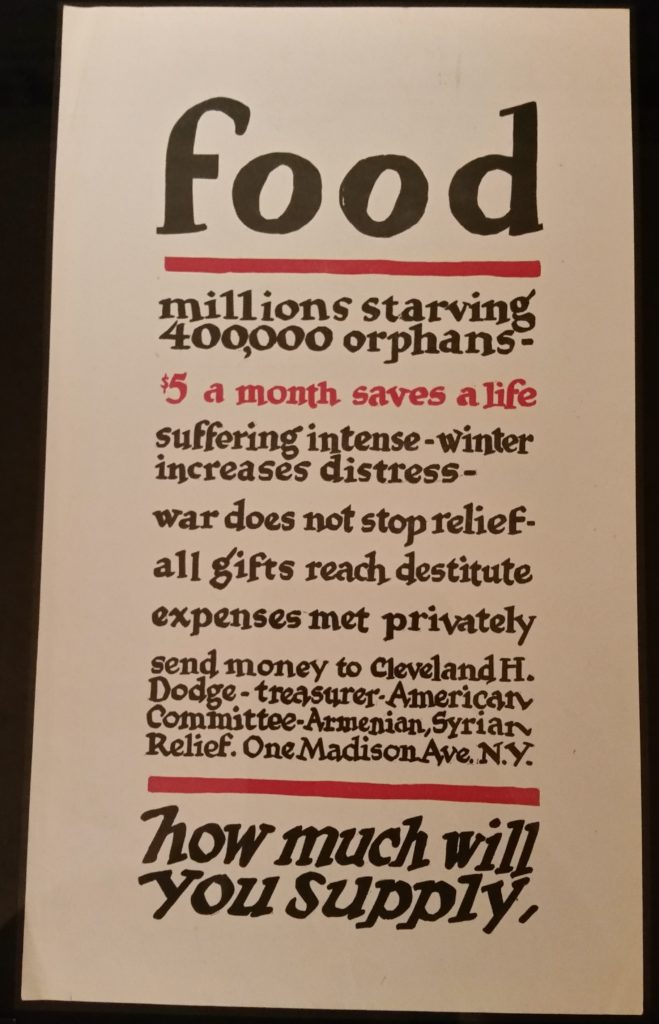

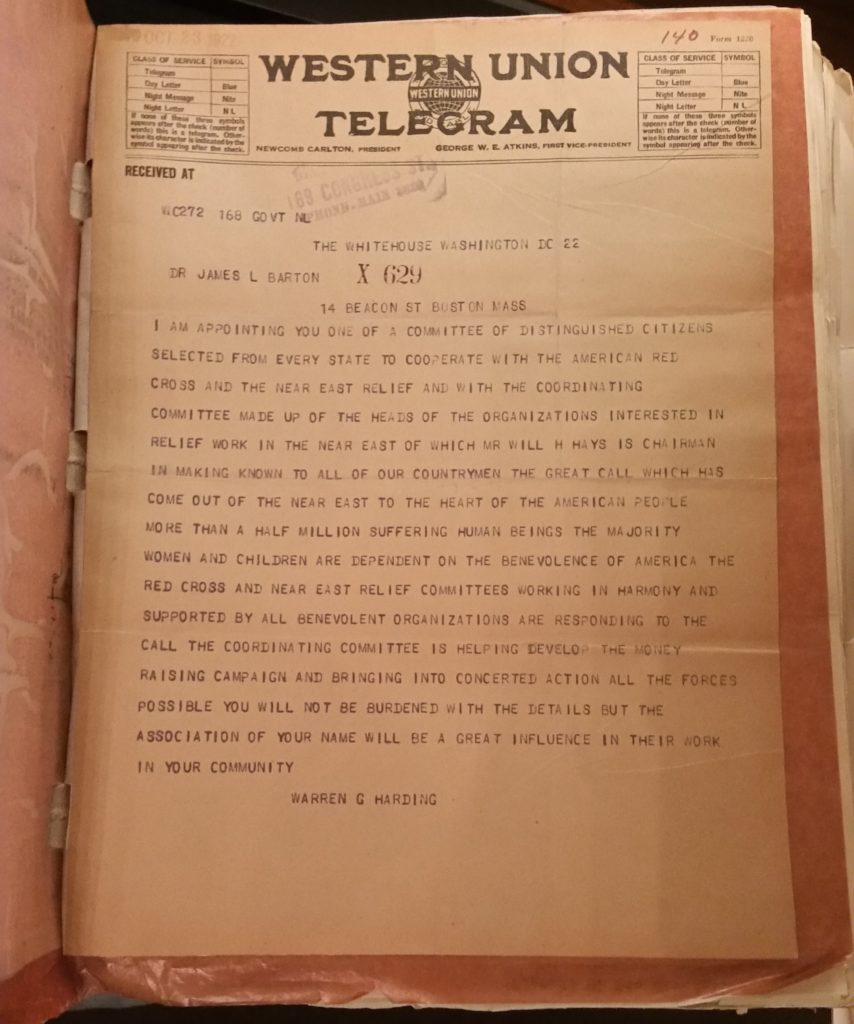

A display case, bearing the title Seeking Asylum, uses the Armenian case to focus on the World War I period and in particular the first major genocide of the 20th century. Hundreds of thousands of Armenians were displaced and had to seek asylum throughout the world, including in the United States. The case includes a 1922 telegram from US President Warren G. Harding to Dr. James L. Barton concerning relief work in the Near East.

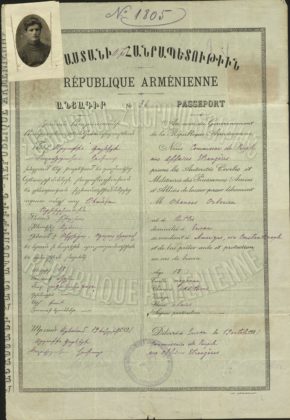

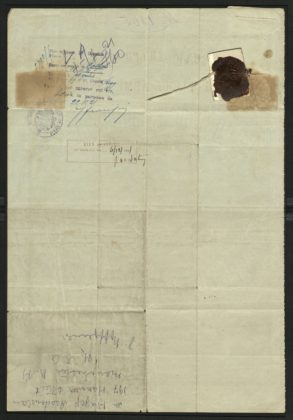

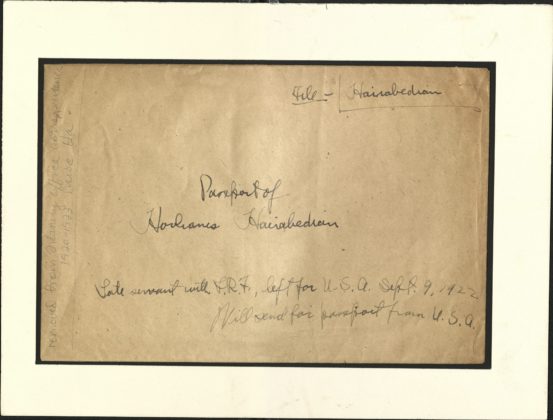

It has a bilingual passport originally printed by the Republic of Armenia but modified by Soviet authorities to indicate that the issuer is the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. The holder, Ohaness Orberian [Vorperian] of Bitlis, also known as Hovhannes Hairabedian, traveled with it from Yerevan to Constantinople and then to the United States. The organizers of the exhibition would be interested to know if any readers might be aware of the subsequent details of the life of Hairabedian/Orberian in the US. They have found that, according to a notice in the newspaper Hairenik, accessed through the Armenian Immigration Project, in 1919 Misak Baghdasarian of Manchester, New Hampshire was seeking him.

There is further information on a Hovhanes Hanabedian [Hairabedian], possibly the same person, coming to Manchester, New Hampshire in 1922, and on the same individual studying at the University of New Hampshire in Durham in 1924.

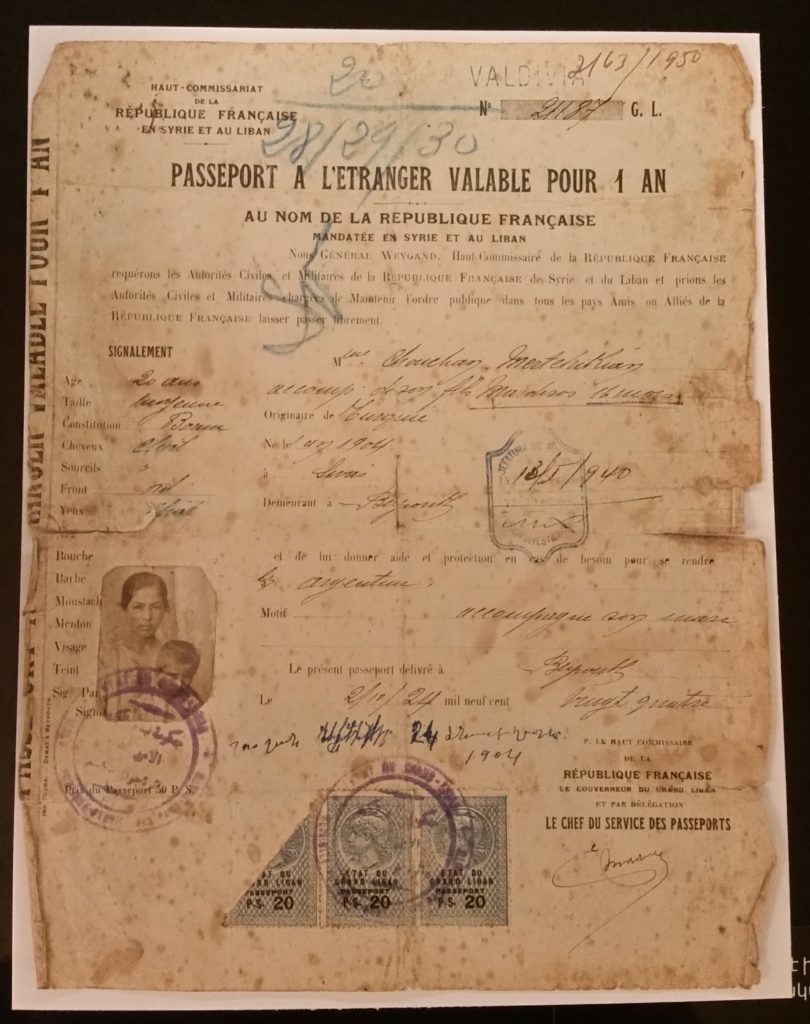

Another interesting item on display is the temporary passport of 18-year-old Suschan Mertehikian [Shushan Mardigian] of Sivas (Sepasdia) and her son Mardiros, aged 16 months and born in Lebanon in 1922, issued by the High Commission of the French Republic in Syria and Lebanon. Suschan had met her husband Ardashess in Lebanon while he was serving in the French army. He had joined the French Foreign Legion but had already moved to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he awaited the rest of his family. In 1924 they joined Mardiros. Mardiros passed away in Buenos Aires in 2013.