By Janelle Nanos

BOSTON (Boston Globe) — The markets may fluctuate in the Financial District, but one thing remains consistent. Be it bull or bear, the titans of industry need their suits, and for the last 84 years, they bought them at Zareh.

Bob Kraft and John Fish are clients. Bobby Orr was, too. Mayors Kevin White and John Hynes shopped there. Alan Shepard donned Zareh’s when he wasn’t sporting a spacesuit.

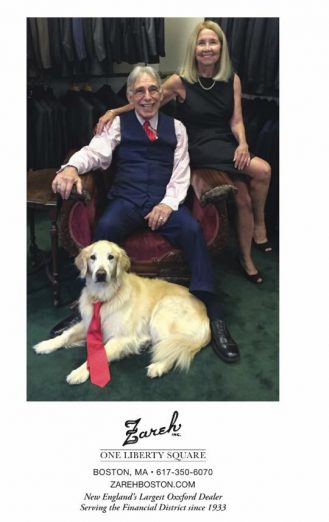

For the last 58 years, Monday through Friday, between the hours of 9 and 5, the dashing haberdasher behind the counter has been Greg Thomajan, who inherited the business from his father in the 1970s. So it was with a heavy heart that Thomajan began telling his customers that he’ll retire at year’s end, closing the store and ending an era.

“My happiest day of the week is Monday morning,” he said one recent morning, ever dapper in a three-piece navy suit. “But an 81-year-old gentleman who signs a five-year lease should have his head examined.”

Thomajan’s father, Zareh, opened his store on State Street in 1933, selling gabardine shirts for $7.50. Today, the suits at One Liberty Square start at $3,500, off the rack, but the store looks much as it always has: the plush green carpets of a country club; handsome wooden cases stocked with button-downs; crystal chandeliers dangling over the racks of Oxxford suits, illuminating subtle gradations of blue and gray. The store’s mascot, a 7-month-old golden retriever named Skipper, channels his energy into a chew toy.